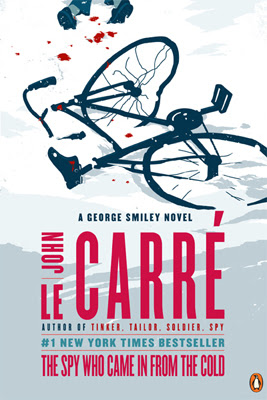

Book Review: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold by John le Carré (1963)

John le Carré was still working for MI6 when he wrote his first two novels, Call for the Dead and A Murder of Quality, both of which focused on George Smiley. (You can read more about him here.) Apparently those books painted a bleak enough portrait of the British Secret Service, or “Circus,” as le Carré calls it (in the case of the former), and Britain’s class-fuelled society (mainly in the second) for le Carré’s mentor, author and fellow spook John Bingham, to disown his protégé entirely. But read today, they really don’t seem all that incendiary. It was with his third and most famous book, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, that the author would launch his all-out assault on the glamorous world of espionage as popularized in the bestselling novels of Ian Fleming. Le Carré wanted to expose the secret world of the British Secret Service as the seedy, hypocritical establishment he felt he saw around him every day. His hero, Alec Leamas, would not drive a Bentley or Aston Martin, would not be too fastidious about whether he took his martinis shaken or stirred (or even if his alcohol was mixed into a martini to begin with), and would not hold or use a license to kill. Despite being (or at least intended as being) a sort of anti-Bond, however—and despite spending a whole chapter pathetically laid up with a fever and subsisting on Bovril in a squalid Bayswater flat, Alec Leamas did share one crucial element with his rival: his world, however seedy, was breathtakingly exciting.

While The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is just as exciting as a Bond book, though, it is not as accessible. Which means, for my purposes, that it isn’t nearly as appealing to a twelve-year-old boy. I first attempted this book when I was in the midst of discovering James Bond and the spy genre at large, voraciously tearing through the works of Ian Fleming and Robert Ludlum, whose books I’d moved onto directly from the Hardy Boys. There was a copy of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold on one of my parents’ bookshelves, and I’d heard of le Carré, so I thought I might find something on par with the Bond and Bourne adventures I’d been reading. Plus, the title was intriguing! What was a spy doing out in the cold to begin with, I wondered? In answer, I probably imagined the beginning of A View to a Kill. I was in for a disappointment. John le Carré is really not the stuff for pre-teens. I was bored out of my mind. That bit where Leamas is laid up, sipping beef tea? It's a whole chapter! Did I mention that? And in the first half of the book, the hero spends more time working in a library and picking fights with local grocers than he does spying. You simply couldn’t go from James Bond fighting a giant squid in Doctor No to Alec Leamas doing time in prison to establish his cover. I was bored out of my mind, and I never finished the book. My first encounter with John le Carré had come at entirely the wrong time in my life. And at that point, I couldn't guess that, though the author would be absolutely loathe to admit it, le Carré's book had more in common with Fleming's than I could grasp.

Years later, however, I was spy-mad once more, and as luck would have it, I was also in a long-distance relationship, which afforded me lots of reading time on flights between Los Angeles and Chicago. And I was determined to give le Carré another chance. This time, I was an adult, I’d been exposed to far more spy literature and far more life, and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was just the thing. This time, I could get excited by spymaster Control’s ingeniously twisty, Machiavellian plan, and even by the previously boring mundanity of Leamas’s day-to-day existence as he plunges into drink and disrepair in order to make himself a tempting target for foreign agents to attempt to turn. If le Carré set out to paint the bleak reality of spying as boring and mundane compared to the sensational exploits of 007, then he succeeded… for schoolboys. But not for adults, I’m afraid, most of whom (at least those who are likewise inclined) probably find the novel as thrilling as I do. However, I don’t think that was his plan. Despite his rants against James Bond in the press at the time, I think le Carré always set out to tell a story just as exciting as Ian Fleming’s, to entertain his readers just as much. He simply uses different tools, paints with a different palette, to achieve the same effect. And though he may not have seen it at the time, there’s clearly room in the wider spy genre for both styles.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold opens with a fiftyish British spy named Alec Leamas waiting at West Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie for the only surviving agent in his network to cross over from the East. Instead, he sees him gunned down at the border. That’s the end of his network and the end of his career. He’s finished. All thanks to a ruthless East German counterspy named Hans-Dieter Mundt—the very same Mundt who slipped through George Smiley’s fingers in London in Call for the Dead. Leamas returns to the Circus in disgrace, burning with hatred for his enemy. Control (as the head of le Carré’s secret service is known) sees an opportunity to channel that hatred, and he recruits Leamas in a private long-game operation targeting Mundt directly—designed to leave him discredited and dead. I’m hesitant to describe too many details of the mission here, because part of the thrill of the book comes from the stinginess with which the author doles them out. (Honestly, le Carré uses this lack of information—playing on our desire to learn it—to the same effect that Fleming uses shootouts and encounters with deadly animals. The results are equally thrilling.) We’re at first led to believe that Leamas really is going to seed, though seasoned spy readers will see through that ploy pretty quickly. But other than realizing that the disgruntled British agent is being made over as a likely candidate for Soviet or East German recruitment, we’re never certain quite where this is going. Nor are we certain if Leamas is certain. But it’s quite a ride to watch it all unfold.

The earlier chapters are dedicated to Leamas’ squalid new (apparently) post-Circus life. Fired from the institution to which he’s dedicated his life (supposedly for stealing from the till), he drinks a lot and moves into a run-down flat. After trying a few jobs and rejecting them, he finally finds one he likes alright shelving esoteric books at a highly specialized library dedicated to “psychic research.” His co-workers there include the disagreeable boss Miss Crail, one of those great, unforgettable le Carré characters you love to hate, and a girl half his age named Liz Gold. Liz quickly falls in love with Leamas, and he indulges her and slowly grows to reciprocate her feelings in his own way. But he’s so reserved about his past, his future and everything that he remains a mystery to the frustrated Liz. That doesn’t stop her from nursing him back to health, though, once he’s stricken with a terrible fever.

Dying to understand what makes him tick, she asks him what he believes in, and he’s non-committal. He turns the question on her, and she says she believes in history. “Oh, Liz… oh no,” he says after a pause, “You’re not a bloody Communist?” And here we come to another similarity between le Carré and Fleming, despite le Carré’s insistence on distancing himself from 007 at every turn. Like Fleming, le Carré truly hates Communism. Since he seems to hate the mechanisms of the Capitalist Western governments just as much, this is sometimes overlooked in critical analyses of the author’s works. It’s true that he’s written some truly damning critiques of Britain and especially America and their behavior during and after the Cold War, but it would be a mistake to confuse anti-Americanism for pro-Communism. Most of le Carré’s books, including this one, demonstrate the tolls that spy games between East and West take on the human beings caught up in the middle. Individuals are frequently crushed by both sides, or destroyed in the conflict between them. But that doesn’t mean le Carré has any love for the East. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold positively drips with a prevailing hatred of the Communist system.

Leamas loves Liz despite her political affiliations, and she, like him, is mercilessly used by both sides. But le Carré’s utter contempt for every level of the Communist machine comes across strongly from scenes of Liz’s harmless but hopelessly disorganized local Party branch in the UK to scenes of an equally ineffectual yet far more dangerous Party meeting in East Germany to an East German secret tribunal right out of Orwell, whereas for the British spymaster Control, who shows little more regard for human lives than the KGB in executing his circuitous schemes, le Carré reserves a grudging but undeniable affection. While it condemns the Circus for using tactics not dissimilar to those of their enemy, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold remains a chillingly effective anti-Communist novel, which may come as a surprise to modern readers who think of le Carré as a left-leaning writer simply because he hates the right.

But is Control truly the architect of this devious, labyrinthine operation? To someone reading le Carré for the first time, it would certainly seem to, as it did to me when I read this book years ago on one of those red-eyes from Chicago. But if you’re reading his books in order, and have Call for the Dead and A Murder of Quality firmly in mind, then George Smiley’s fingerprints become unmistakable. In a column called The Smiley Files, it may seem odd that I’m getting to the paunchy and myopic but brilliant spymaster so late in the game. Unlike in the author’s first two novels, Smiley is not the protagonist of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. For all intents and purposes, in fact, he’s barely a presence in the novel. But then again… he is. Control tells Leamas early on that Smiley wants nothing to do with this operation because he finds it “distasteful.” (“He sees the necessity but he wants no part of it.”) And, given what we know about Smiley from his previous adventures, that certainly seems likely. But given what we learn about him in books to come (notably the “Karla Trilogy”), we know that Smiley isn’t above engaging in activities he finds distasteful if they’re an adequate means to an important end. To a casual reader unfamiliar with le Carré’s other works, there’s every reason to believe Control’s declaration. Such a reader would probably gloss right over the frequent, but seemingly inconsequential moments when Leamas sees “a little sad man with spectacles” or “a small, froglike figure in glasses” out of the corner of his eye or detects “the figure of a man in a raincoat, short and rather plump” who disappears into the shifting mist upon closer inspection. But Smiley devotees will recognize his presence again and again throughout the book, and will probably wonder exactly how large a role he really plays in masterminding the intricate scheme.

This is but one of several reasons that I’d recommend reading at least Call for the Dead before The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, despite the fact that Spy is the better book. Besides establishing a familiarity with George Smiley that enhances the reader’s grasp on the plot, Call for the Dead also provides an operational background on Mundt that makes the later book more rewarding. Furthermore, having read that one, readers will appreciate the call-backs and cameos from other recurring characters, like Peter Guillam.

Ultimately, though, it isn’t character cameos or the question of how involved George Smiley really is in the Leamas operation that makes The Spy Who Came in from the Cold such a compelling spy novel and, indeed, the template for half the books written in the genre after it. What makes it great reading—and absolutely essential reading for fans of the genre—is that operation itself, and the way the author slowly reveals its nature to his audience by peeling back layers. It’s a fascinating look at the actual workings of espionage and tradecraft that you certainly won’t get from James Bond. And, frankly, Control’s (or Smiley’s) scheme is far more ingenious than any operation M ever sends 007 off on. It’s this thrillingly realistic depiction of a plausible intelligence operation that earned le Carré his reputation as an expert in the field and a realistic chronicler of its practitioners. As the author himself later recalled, it wasn’t because the story was true that it bothered the real world spooks (if he were, he points out, he never would have been allowed to publish it); it was because it could be true. It was plausible. It’s this plausibility combined with a gifted storyteller’s imagination that makes it such compelling reading. Perhaps there are bicycles instead of Bentleys and Bovril instead of dry martinis, but this is still a spy story told by a writer with an imagination every bit as vivid as Ian Fleming’s—and therefore, however gritty and tawdry, still to some degree an escapist fantasy. For a truer-to-life depiction of the sorts of actual operations to which le Carré was witness in his own spy days, readers would have to wait until his next novel (also featuring Smiley in a reduced role), The Looking Glass War. And the only way to deliver that level of depressing truth, the author must have realized, was through a more satirical point of view than readers were yet accustomed to from the author of the page-turning Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

The Smiley Files

Part 1: George Smiley: An Introduction

Part 2: Movie Review: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Part 3: Book Review: Call for the Dead (1961)

Part 4: Movie Review: The Deadly Affair (1966)

Part 5: Book Review: A Murder of Quality (1962)

Part 6: Movie Review: A Murder of Quality (1991)

Apr 11, 2012

Book Review: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963)

Labels:

Books,

John Le Carre,

Reviews,

Sixties,

Smiley

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

Can't wait to check out the "The Spy Who Came in from the Cold." Just finished "The Rx Factor " by J. Thomas Shaw, and am hooked on political thrillers. Thanks for the great suggestion.

Nice review, but I don#t agree with your thoughts on Smiley's possible involvement.

I think especially his development in the later books strongly suggests that he really finds the whole operation distasteful and wants no part of it. if he is already as ruthless as he is in the later books during the period in which "The Spy who..." is set, his later character arc in the Karla triology loses most of its power IMO.

It's true that an increased involvement undermines that later character arc a bit, but I think that comes mainly from le Carre not having thought out that arc yet. As many have pointed out, he SORT OF "reboots" the characters in the Karla trilogy. But read TSWCIFTC again, and you'll catch all those hidden glimpses of Smiley! I think it's pretty clear that he's far more involved than Control lets on. Why else would he be the one at the end?

Post a Comment