Dorado Films, the DVD genre specialists who introduced several great Eurospy movies to North American home video audiences over the last several years, are now streaming some of their titles on YouTube for free! (See all the YouTube "screeners" currently available here.) Besides a title included in their essential DVD box set How Europe Does BABES, BOMBS, and GUNS, but never released on its own (Elektra 1), these online screeners also include two highly sought-after Ken Clark titles yet to see DVD release: Tiffany Memorandum (1967) and The Fuller Report (1968). Clark does not reprise his Special Mission Lady Chaplin/From the Orient with Fury/Mission Bloody Mary character of "Dick Malloy, Agent 077" in these movies, but instead plays a pair of amateurs caught up in international espionage (a journalist in the former, and a race car driver in the latter). Both films are directed by Sergio Grieco, and both are well worth watching! In fact, watch them a few times, leave comments, and tell your friends. Dorado is using these YouTube screeners to measure the demand for these films. If these Eurospy titles get a lot of views online, then Dorado will know that it's worth investing in the titles to produce high quality, widescreen DVDs. (The screener versions are watermarked fullscreen TV prints from 1" broadcast tapes.) So take advantage of Dorado's generosity and sample their library for free, and at the same time let them know you like these Eurospy titles and that you want to see more! It's a win/win scenario for fans and the distributor alike!

You can also stream Dorado's widescreen releases of Mission Bloody Mary and From the Orient with Fury on Amazon.

Double O Section is a blog for news and reviews of all things espionage–-movies, books, comics, TV shows, DVDs, and everything else.

Apr 30, 2012

Apr 23, 2012

First Skyfall Magazine Cover

It's begun! Empire has bragging rights for the first Skyfall magazine cover in what's sure to be a 50th Anniversary-fueled onslaught of Bondian hype. And I'll end up buying every magazine to slap 007 on its cover, as I always do... starting with this one. Here's what they say about the James Bond content inside on the Empire website:

Hear that? Dalton interview! Awesome. This issue hits UK newsstands on Thursday, and will no doubt wash up Stateside shortly thereafter. Keep your eyes peeled!

Inside we have the fruit of several visits to the set of Skyfall, wherein we try to peer behind the veil of secrecy that covers the production (well, it is about a spy after all) and bring you all the news we can extract from the cast and crew. We also celebrate Bond's 50th anniversary with a look at some key moments in Bond history: there's a look at GoldenEye, Live and Let Die and On Her Majesty's Secret Service, as well as a chat with Timothy Dalton. You might say we have a licence to thrill! If you were into tired puns, anyway.

Hear that? Dalton interview! Awesome. This issue hits UK newsstands on Thursday, and will no doubt wash up Stateside shortly thereafter. Keep your eyes peeled!

Apr 20, 2012

James Bond On the Big Screen in San Francisco This Weekend

FRIDAY APRIL 20 DOUBLE FEATURE

• DR. NO 2:00, 7:00

• ON HER MAJESTY’S SECRET SERVICE 4:10, 9:05

SATURDAY APRIL 21 TRIPLE FEATURE

($11 General / $8 Kids & Seniors)

• FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE 2:30, 9:30

• DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER 4:45

• THE SPY WHO LOVED ME 7:05

SUNDAY APRIL 22 TRIPLE FEATURE

($11 General / $8 Kids & Seniors)

• THUNDERBALL 1:00, 8:15

• LIVE AND LET DIE 3:30

• FOR YOUR EYES ONLY 5:50

I highly recommend that last one. I had the chance to see For Your Eyes Only on the big screen in a gorgeous film print a few years ago, and it was nothing short of revelatory. I've always been a fan of FYEO, but that screening elevated it to the position of my favorite Roger Moore movie. Fantastic!

• DR. NO 2:00, 7:00

• ON HER MAJESTY’S SECRET SERVICE 4:10, 9:05

SATURDAY APRIL 21 TRIPLE FEATURE

($11 General / $8 Kids & Seniors)

• FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE 2:30, 9:30

• DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER 4:45

• THE SPY WHO LOVED ME 7:05

SUNDAY APRIL 22 TRIPLE FEATURE

($11 General / $8 Kids & Seniors)

• THUNDERBALL 1:00, 8:15

• LIVE AND LET DIE 3:30

• FOR YOUR EYES ONLY 5:50

I highly recommend that last one. I had the chance to see For Your Eyes Only on the big screen in a gorgeous film print a few years ago, and it was nothing short of revelatory. I've always been a fan of FYEO, but that screening elevated it to the position of my favorite Roger Moore movie. Fantastic!

Thanks to Doug and Spy Vibe's Jason for the heads-up.

Apr 19, 2012

New Skyfall Video Blog Reveals Some Film Footage

It's not a trailer, but this latest video blog from 007.com, the film's official site, featuring 2nd Unit Director Alexander Witt, reveals some very cool, very Bondian, very beautiful scenic shots of Shanghai, one of the thrilling cities Daniel Craig's James Bond visits in Skyfall. As with everything else we've seen so far from this film, it looks great to me!

Apr 17, 2012

Book Review: The Looking Glass War by John le Carré (1965)

Book Review: The Looking Glass War by John le Carré (1965)

Critics in 1965 saw The Looking Glass War as something of a departure for John le Carré following the breakout universal success of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. In his 1990s introduction to the book, the author claims they weren’t happy about that—not in Britain anyway. Everyone wanted the same thing from him again, and he wanted to give them something different. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold had depicted in great detail a highly successful and wickedly clever espionage operation masterminded by a man called Control, the ingenious head of an intelligence service known as “the Circus.” Le Carré claims that operations of that sort were not quite what he himself experienced during his years as a spook, during which he worked for both MI5 and MI6. In his follow-up novel, he wanted to present something much closer to the truth as he knew it: a clumsily planned operation carried out by well-meaning fools with delusions of grandeur still fighting the last war in their heads, who haven’t yet learned to properly use the tools of the new (Cold) one. A story of vital opportunities—not to mention lives—lost because of career bureaucrats more focused on inter-agency bickering than gathering good intelligence.

Not only did le Carré change his presentation of the British intelligence establishment; he even changed his tone, trading in the bleak, urgent paranoia of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold for extra-dry satire with a vicious bite. (Somewhat reminiscent of his take on another British institution, the public school, in A Murder of Quality.) The new approach caught contemporary critics and readers off guard. If he had it to do again, le Carré writes in his introduction, he would probably opt to leave out returning characters like Control and George Smiley altogether, along with any mention of the Circus, presumably so as to firmly set The Looking Glass War in its own separate literary universe and not raise false expectations in readers familiar with his previous work. Thank goodness he didn’t get the opportunity to do it again, like he did with A Murder of Quality (when he penned the screenplay for its 1991 TV adaptation)! The Looking Glass War is a very good novel as it stands now, and some of the best moments and sharpest satire come directly from his use of those pre-established characters and organizations.

Never mentioning real-world monikers like “MI6” or “SIS,” le Carré always refers to George Smiley’s organization simply as “the Circus.” Likewise, the arm of the intelligence establishment explored in The Looking Glass War is also known only by a colloquialism: “the Department.” (This could be a little confusing to readers of the author’s wider Smiley series, since the Circus itself is often referred to as “the Department” as well in other novels, but for the purposes of The Looking Glass War, those names refer strictly to two very different intelligence agencies.) The Department is concerned exclusively with intelligence on military targets, and though it ran a lot of missions during WWII (sort of like the SOE, I guess), its primary concern by the 1960s is analysis rather than intelligence gathering. It’s an old department housed in an old building and made up of old men, all veterans of those halcyon days of the War… except for one.

The protagonist is John Avery, the Department’s youngest employee and as such its rising star. Avery is the aide to the Director of the Department, Leclerc. Leclerc is fed up with seeing his former responsibilities one by one subsumed by the Circus. He longs to return his organization to its wartime strength, and sees an opportunity to do just that when one of his few remaining field men (all remnants of defunct wartime networks, naturally) turns in a report containing a defector’s eyewitness account of Soviet missiles being secretly installed in a rural part of East Germany. Rather than turning this report over to the Circus for some sort of corroboration, Leclerc becomes fiercely territorial, claims that since the potential target is military, it is his purview, and launches his own operation. The first agent dispatched (to meet an asset in Finland) turns up dead, which in itself is enough in Leclerc’s mind to confirm that his suspicions are correct and there’s a basis for further action. Leclerc declares that the Department will have to send a man in, behind the Iron Curtain, to obtain confirmation of the intel.

Standard contemporary protocol would dictate turning over such a mission to the Circus, who have many experienced field men used to exactly that sort of assignment. (In fact, Alec Leamas even gets a mention as a potential candidate!) But pride and jealousy prevent Leclerc from doing that. Officially, he convinces his Ministry that mixing up the two agencies’ purviews would create a “monolith,” but his real reasons are less civic-minded: he wants a chauffeured car like the one Control has. He wants a budget like Control’s. He wants a building that’s not falling apart. In short, he wants to command the same respect he imagines that Control commands.

These moments of interdepartmental jealousy are highlights of the novel for students of le Carré’s oeuvre, and they work specifically because readers are already familiar with the organizations and characters in question. We know from previous books that the people who work at the Circus don’t consider it to be very luxurious or well-heeled itself. (There isn’t even a budget to keep its headquarters properly heated in the winter!) So to then see a flipside of that, to realize that there are other departments even worse off who see the Circus’s grass as so much greener, provides the reader with both comedy and instant identification. How many of us have not had similar moments of professional jealousy at our own jobs? Half the joke would be lost if we didn’t already know that Control has to light a fire himself if he wants his office to warm up, and that Smiley has to deal with image-conscious idiots like Maston who would happily allow an enemy spy to remain at large for the sake of avoiding embarrassment. Le Carré is able to take advantage of his own canon to provide helpful shorthand in his satire. For all of Smiley’s misery in his job, who would have guessed that there are others in his profession even worse off?

Leclerc and his team dig deep into the Department files and recruit a Polish-born agent who served them well during the War named Leiser. He seems (to them, anyway) the perfect man to penetrate the East. Avery is tasked with babysitting him during his training. But more than that, it’s his role to form a bond with Leiser. Leclerc and his more worldly-wise associate, Haldane, understand that such a bond is integral in fostering an agent’s loyalty. Avery doesn’t realize that he’s being used in this manner.

Seasoned spy readers (especially those familiar with Graham Greene's Our Man in Havana or le Carré's own later reworking of that story, The Tailor of Panama) will spot enough obvious clues along the way to be reasonably sure going into Part III of the novel's three parts that the original intelligence is probably bad, and there will be no missiles, which causes the story to lose a bit of momentum as it follows Leiser on what we strongly suspect is a fool’s errand. But the section leading up to what we’re sure will be a disaster is rich in both character and satire. We witness with equal parts humor and dread as Leiser is trained by experts the Department has dragged out of their comfortable civilian lives to teach the same techniques they taught or used during the War. In one respect, The Looking Glass War sets the template (more than The Spy Who Came in from the Cold) for future le Carré novels: we know from the start that the idealistic protagonist (or one of them, anyway) is doomed in this world, and the big question of the novel is not if that doom will come but how. While the author frequently plays this scenario for dread, here he plays it more for dark comedy. He doesn’t comment on what Leclerc and his Department do wrong; instead he makes it obvious even to people (the majority of his readers, presumably) with no experience in the intelligence field. It’s like watching a car crash in slow motion. We can’t stop it, but we’re fascinated by it nonetheless.

The Looking Glass War isn’t all dark comedy, however. It functions on two levels: as a very sharp satire, and, only slightly less successfully, as a love story between two heterosexual men, Leiser and Avery. Their bond isn’t a homosexual bond like that between Hayden and Prideaux in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy; it’s a deep platonic connection. And, for these two lonely men at this particular place and time, it proves to be a deeper connection than they share with the women in their lives. A part of Leiser knows that he’s going to his doom (in some sense of the word, anyway; “doom” doesn’t necessarily imply “death”), but for Avery, he will willingly do so. That’s exactly what Leclerc and Haldane are counting on, and it makes The Looking Glass War as much a tragedy as a comedy. Again, that leads me to believe that the inclusion of Smiley and Control was integral to the book. Without them, the best comic elements would have been lost, and the story would have risked turning too bleak.

As for Smiley, he actually gets considerably more “screen time” in this novel than he did in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, though his role is less integral to the overall mechanics of the story, if not the tone. He’s also clearly Control’s right-hand man at the Circus, which makes this our only glimpse of the era referred to so frequently in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, when the two enjoyed a successful partnership at the helm of the ship. Smiley has no cause to resign, for once, though he does have the regrettable task of delivering some very bad news. Despite the character’s limited appearance, The Looking Glass War is not a book that Smiley fans should pass over, nor is it a novel that fans of le Carré should overlook. When it comes to Smiley, however, the best (of course), was still yet to come...

The Smiley Files

Part 1: George Smiley: An Introduction

Part 2: Movie Review: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Part 3: Book Review: Call for the Dead (1961)

Part 4: Movie Review: The Deadly Affair (1966)

Part 5: Book Review: A Murder of Quality (1962)

Part 6: Movie Review: A Murder of Quality (1991)

Part 7: Book Review: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963)

Critics in 1965 saw The Looking Glass War as something of a departure for John le Carré following the breakout universal success of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. In his 1990s introduction to the book, the author claims they weren’t happy about that—not in Britain anyway. Everyone wanted the same thing from him again, and he wanted to give them something different. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold had depicted in great detail a highly successful and wickedly clever espionage operation masterminded by a man called Control, the ingenious head of an intelligence service known as “the Circus.” Le Carré claims that operations of that sort were not quite what he himself experienced during his years as a spook, during which he worked for both MI5 and MI6. In his follow-up novel, he wanted to present something much closer to the truth as he knew it: a clumsily planned operation carried out by well-meaning fools with delusions of grandeur still fighting the last war in their heads, who haven’t yet learned to properly use the tools of the new (Cold) one. A story of vital opportunities—not to mention lives—lost because of career bureaucrats more focused on inter-agency bickering than gathering good intelligence.

Not only did le Carré change his presentation of the British intelligence establishment; he even changed his tone, trading in the bleak, urgent paranoia of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold for extra-dry satire with a vicious bite. (Somewhat reminiscent of his take on another British institution, the public school, in A Murder of Quality.) The new approach caught contemporary critics and readers off guard. If he had it to do again, le Carré writes in his introduction, he would probably opt to leave out returning characters like Control and George Smiley altogether, along with any mention of the Circus, presumably so as to firmly set The Looking Glass War in its own separate literary universe and not raise false expectations in readers familiar with his previous work. Thank goodness he didn’t get the opportunity to do it again, like he did with A Murder of Quality (when he penned the screenplay for its 1991 TV adaptation)! The Looking Glass War is a very good novel as it stands now, and some of the best moments and sharpest satire come directly from his use of those pre-established characters and organizations.

Never mentioning real-world monikers like “MI6” or “SIS,” le Carré always refers to George Smiley’s organization simply as “the Circus.” Likewise, the arm of the intelligence establishment explored in The Looking Glass War is also known only by a colloquialism: “the Department.” (This could be a little confusing to readers of the author’s wider Smiley series, since the Circus itself is often referred to as “the Department” as well in other novels, but for the purposes of The Looking Glass War, those names refer strictly to two very different intelligence agencies.) The Department is concerned exclusively with intelligence on military targets, and though it ran a lot of missions during WWII (sort of like the SOE, I guess), its primary concern by the 1960s is analysis rather than intelligence gathering. It’s an old department housed in an old building and made up of old men, all veterans of those halcyon days of the War… except for one.

The protagonist is John Avery, the Department’s youngest employee and as such its rising star. Avery is the aide to the Director of the Department, Leclerc. Leclerc is fed up with seeing his former responsibilities one by one subsumed by the Circus. He longs to return his organization to its wartime strength, and sees an opportunity to do just that when one of his few remaining field men (all remnants of defunct wartime networks, naturally) turns in a report containing a defector’s eyewitness account of Soviet missiles being secretly installed in a rural part of East Germany. Rather than turning this report over to the Circus for some sort of corroboration, Leclerc becomes fiercely territorial, claims that since the potential target is military, it is his purview, and launches his own operation. The first agent dispatched (to meet an asset in Finland) turns up dead, which in itself is enough in Leclerc’s mind to confirm that his suspicions are correct and there’s a basis for further action. Leclerc declares that the Department will have to send a man in, behind the Iron Curtain, to obtain confirmation of the intel.

Standard contemporary protocol would dictate turning over such a mission to the Circus, who have many experienced field men used to exactly that sort of assignment. (In fact, Alec Leamas even gets a mention as a potential candidate!) But pride and jealousy prevent Leclerc from doing that. Officially, he convinces his Ministry that mixing up the two agencies’ purviews would create a “monolith,” but his real reasons are less civic-minded: he wants a chauffeured car like the one Control has. He wants a budget like Control’s. He wants a building that’s not falling apart. In short, he wants to command the same respect he imagines that Control commands.

These moments of interdepartmental jealousy are highlights of the novel for students of le Carré’s oeuvre, and they work specifically because readers are already familiar with the organizations and characters in question. We know from previous books that the people who work at the Circus don’t consider it to be very luxurious or well-heeled itself. (There isn’t even a budget to keep its headquarters properly heated in the winter!) So to then see a flipside of that, to realize that there are other departments even worse off who see the Circus’s grass as so much greener, provides the reader with both comedy and instant identification. How many of us have not had similar moments of professional jealousy at our own jobs? Half the joke would be lost if we didn’t already know that Control has to light a fire himself if he wants his office to warm up, and that Smiley has to deal with image-conscious idiots like Maston who would happily allow an enemy spy to remain at large for the sake of avoiding embarrassment. Le Carré is able to take advantage of his own canon to provide helpful shorthand in his satire. For all of Smiley’s misery in his job, who would have guessed that there are others in his profession even worse off?

Leclerc and his team dig deep into the Department files and recruit a Polish-born agent who served them well during the War named Leiser. He seems (to them, anyway) the perfect man to penetrate the East. Avery is tasked with babysitting him during his training. But more than that, it’s his role to form a bond with Leiser. Leclerc and his more worldly-wise associate, Haldane, understand that such a bond is integral in fostering an agent’s loyalty. Avery doesn’t realize that he’s being used in this manner.

Seasoned spy readers (especially those familiar with Graham Greene's Our Man in Havana or le Carré's own later reworking of that story, The Tailor of Panama) will spot enough obvious clues along the way to be reasonably sure going into Part III of the novel's three parts that the original intelligence is probably bad, and there will be no missiles, which causes the story to lose a bit of momentum as it follows Leiser on what we strongly suspect is a fool’s errand. But the section leading up to what we’re sure will be a disaster is rich in both character and satire. We witness with equal parts humor and dread as Leiser is trained by experts the Department has dragged out of their comfortable civilian lives to teach the same techniques they taught or used during the War. In one respect, The Looking Glass War sets the template (more than The Spy Who Came in from the Cold) for future le Carré novels: we know from the start that the idealistic protagonist (or one of them, anyway) is doomed in this world, and the big question of the novel is not if that doom will come but how. While the author frequently plays this scenario for dread, here he plays it more for dark comedy. He doesn’t comment on what Leclerc and his Department do wrong; instead he makes it obvious even to people (the majority of his readers, presumably) with no experience in the intelligence field. It’s like watching a car crash in slow motion. We can’t stop it, but we’re fascinated by it nonetheless.

The Looking Glass War isn’t all dark comedy, however. It functions on two levels: as a very sharp satire, and, only slightly less successfully, as a love story between two heterosexual men, Leiser and Avery. Their bond isn’t a homosexual bond like that between Hayden and Prideaux in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy; it’s a deep platonic connection. And, for these two lonely men at this particular place and time, it proves to be a deeper connection than they share with the women in their lives. A part of Leiser knows that he’s going to his doom (in some sense of the word, anyway; “doom” doesn’t necessarily imply “death”), but for Avery, he will willingly do so. That’s exactly what Leclerc and Haldane are counting on, and it makes The Looking Glass War as much a tragedy as a comedy. Again, that leads me to believe that the inclusion of Smiley and Control was integral to the book. Without them, the best comic elements would have been lost, and the story would have risked turning too bleak.

As for Smiley, he actually gets considerably more “screen time” in this novel than he did in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, though his role is less integral to the overall mechanics of the story, if not the tone. He’s also clearly Control’s right-hand man at the Circus, which makes this our only glimpse of the era referred to so frequently in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, when the two enjoyed a successful partnership at the helm of the ship. Smiley has no cause to resign, for once, though he does have the regrettable task of delivering some very bad news. Despite the character’s limited appearance, The Looking Glass War is not a book that Smiley fans should pass over, nor is it a novel that fans of le Carré should overlook. When it comes to Smiley, however, the best (of course), was still yet to come...

The Smiley Files

Part 1: George Smiley: An Introduction

Part 2: Movie Review: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Part 3: Book Review: Call for the Dead (1961)

Part 4: Movie Review: The Deadly Affair (1966)

Part 5: Book Review: A Murder of Quality (1962)

Part 6: Movie Review: A Murder of Quality (1991)

Part 7: Book Review: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963)

Apr 15, 2012

Upcoming Spy DVDs: Safe House

Read my review of Safe House here.

Apr 13, 2012

Tradecraft: Harrison Ford and Gary Oldman Circle Corporate Espionage Movie

According to The Hollywood Reporter, former Air Force One rivals Harrison Ford (Patriot Games) and Gary Oldman (Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy) are circling an industrial espionage thriller called Paranoia, to be directed by Robert Luketic. The Hunger Games' Liam Hemsworth is also in the mix, adding a draw for the youth market for whom the combination of Indiana Jones and George Smiley isn't enough on its own. All the trade reveals about the plot is that it's "a corporate espionage thriller set in the world of dueling telecom giants," but it appears to be based on a book by spy writer Joseph Finder. (I've read other Finder books, but not that one.) Luketic's more famous for romantic comedies like Legally Blonde, but his previous spy experience includes directing the Ashton Kutcher flop Killers and flirting at one point with the forever-in-the-works Matt Helm reboot, at that time set to star Josh Duhamel.

William Boyd to Write the Next James Bond Continuation Novel

I'm traveling right now and thought I had this blog well covered with a few evergreen, non time sensitive posts in the pipeline, but the literary and filmic curators of James Bond seem determined to prove I picked the wrong time to travel with all sorts of big reveals and announcements this week! In addition to the slew of Skyfall stills that MGM released, Ian Fleming Publications made a huge announcement yesterday, reported by The Book Bond (a truly excellent resource for all sorts of information on the literary 007, from the latest breaking news, like this, to detailed examinations of older editions by Fleming and his followers, which I check religiously every day): esteemed British author William Boyd has been selected by IFP to pen the next James Bond novel. The untitled book, due to be published in Fall 2013 by Jonathan Cape in the UK and HarperCollins in the USA, will return 007 to his 1960s roots. The last time we got a historical Bond novel by an artsy, award-winning author, the result was Sebastian Faulks' Devil May Care, a crude Fleming pastiche I didn't care for one bit. But I'm much more hopeful about Boyd's take on the most famous literary secret agent of all time. Faulks was dismissive of the assignment from the start, making it clear in every interview that his book was a literary lark for him, and he considered himself well above the material. Boyd, however, has demonstrated a clear passion for Ian Fleming over the years, and used Fleming as a character in his novel Any Human Heart. (In the 2011 TV adaptation, Fleming was played by Casino Royale co-star Toby Menzies.) I'm somewhat ashamed to admit that I haven't read Any Human Heart, though it's been in my Amazon wishlist since its 2004 publication. I've never read anything by Boyd, but I'm certainly eager to see his take on Ian Fleming's incredible creation.

The most recent James Bond continuation novel was last year's Carte Blanche by Jeffery Deaver, which somewhat rebooted the series in a contemporary setting. Some fans seem surprised that IFP would go back to a period setting (Boyd's untitled book is set in 1969, shortly after Fleming left off and shortly after the events of Devil May Care, if the new author chooses to acknowledge or reference them in any way) after Deaver's much ballyhooed but blessedly not very drastic "reboot." I'm not. The current regime at IFP seem keen to explore numerous creative possibilities with different authors (besides the Deaver and Faulks books, they've brought us Charlie Higson's Young Bond series and Samantha Weinberg's Moneypenny Diaries, both of which were offbeat, but very, very good), and as long as they keep selecting exciting writers, it makes sense to let each writer decide on his or her own approach, including the period. That said, reading between the lines of remarks that Deaver made on his Carte Blanche book tour, I wouldn't be at all surprised if he or someone else picked up where that book left off in a few years with another new contemporary Bond thriller. Hopefully the reading public is sophisticated enough to grasp the notion of two (or more) timelines running at once. Personally, I'm overjoyed. I hope they keep hiring interesting and well-regarded authors to pen one-off Bond novels. It gives fans the opportunity to read a lot of different takes on their favorite spy hero. And I'm including Faulks among the interesting authors. I may not have liked his take, personally, but the beauty of this model is that there's always another take I might prefer right around the corner. This rotating novelist plan still leaves the doors open for the likes of Mark Gatiss, Lee Child, Stephen Fry, Jeremy Duns, Charlie Higson (who has yet to tackle the adult 007) and any number of authors I'd love to see tackle a Bond novel! Who knows? Maybe they'll even entice notorious Bond hater John le Carré to take a crack and show us how he would do it... The possibilities remain endless. (Though, I'll admit, that last one I mentioned seems really unlikely!)

Additionally, The Book Bond also reports that IFP is looking to continue the Young Bond series started by Higson... but, unfortunately, with a new author. Higson apparently confirmed this in a tweet, acknowledging that they couldn't wait forever for his schedule to free up. The search is on for that new author.

The most recent James Bond continuation novel was last year's Carte Blanche by Jeffery Deaver, which somewhat rebooted the series in a contemporary setting. Some fans seem surprised that IFP would go back to a period setting (Boyd's untitled book is set in 1969, shortly after Fleming left off and shortly after the events of Devil May Care, if the new author chooses to acknowledge or reference them in any way) after Deaver's much ballyhooed but blessedly not very drastic "reboot." I'm not. The current regime at IFP seem keen to explore numerous creative possibilities with different authors (besides the Deaver and Faulks books, they've brought us Charlie Higson's Young Bond series and Samantha Weinberg's Moneypenny Diaries, both of which were offbeat, but very, very good), and as long as they keep selecting exciting writers, it makes sense to let each writer decide on his or her own approach, including the period. That said, reading between the lines of remarks that Deaver made on his Carte Blanche book tour, I wouldn't be at all surprised if he or someone else picked up where that book left off in a few years with another new contemporary Bond thriller. Hopefully the reading public is sophisticated enough to grasp the notion of two (or more) timelines running at once. Personally, I'm overjoyed. I hope they keep hiring interesting and well-regarded authors to pen one-off Bond novels. It gives fans the opportunity to read a lot of different takes on their favorite spy hero. And I'm including Faulks among the interesting authors. I may not have liked his take, personally, but the beauty of this model is that there's always another take I might prefer right around the corner. This rotating novelist plan still leaves the doors open for the likes of Mark Gatiss, Lee Child, Stephen Fry, Jeremy Duns, Charlie Higson (who has yet to tackle the adult 007) and any number of authors I'd love to see tackle a Bond novel! Who knows? Maybe they'll even entice notorious Bond hater John le Carré to take a crack and show us how he would do it... The possibilities remain endless. (Though, I'll admit, that last one I mentioned seems really unlikely!)

Additionally, The Book Bond also reports that IFP is looking to continue the Young Bond series started by Higson... but, unfortunately, with a new author. Higson apparently confirmed this in a tweet, acknowledging that they couldn't wait forever for his schedule to free up. The search is on for that new author.

Apr 12, 2012

Even More New Skyfall Stills!

Today, MGM and Sony revealed a set of new stills from Skyfall on 007.com. I have to say, based on the images we're seeing, I think Skyfall looks fantastic! Granted, I said that about Quantum of Solace, too, right up through the excellent trailers, and we all know how that turned out... but I've got a good feeling about Skyfall! Also, all of the official stills released so far from the Sam Mendes-directed 23rd Bond film are strikingly beautiful, from their composition to their color palette to their contents, whether that's Bernice Marlohe sashaying through a train station, Naomie Harris firing a pistol from her car or this gorgeous shot of James Bond (Daniel Craig) in front of his Aston Martin DB5 (I'm guessing in Scotland) that appeared on /film. Also worth noting: while Pierce Brosnan drove a DB5 with the license plate "BMT 214A" in GoldenEye and Tomorrow Never Dies and cut scenes of The World Is Not Enough, Daniel Craig's DB5 (first seen in Casino Royale with Bahamanian plates) again bears the license plates from Sean Connery's famous Goldfinger car: BMT 216A. I like that.

Upcoming Spy DVDs: Washington: Behind Closed Doors (1977)

CIA director Bill Martin (Cliff Robertson) knows that an incoming president means a new direction for the country—and another set of eyes on the top secret Primula Report. Martin tries to build a rapport with his new boss, but President Richard Monckton (Jason Robards) is more interested in settling old scores and cleaning house with the help of the FBI. Against the backdrop of a war in Southeast Asia and antiwar protests at home, this high-intensity political drama tells the story of an increasingly paranoid president, an administration under siege, and a reckless group of White House aides desperate to hold on to power.This sounds great! I can't wait to see it. The 3-disc, 6-episode set will retail for $59.99 (though it will no doubt be less on Amazon), and includes an 8-page bonus booklet "with articles on the historical background of the program, the Vietnam War, peace movements in America, Nixon’s visit to China, and the Watergate scandal; plus brief biographies of the political figures of the period." Due to music rights issues, alterations have been made to the original soundtrack. Oh well. That's a small price to pay to have this well-regarded all-star miniseries on home video for the first time in any format!

Apr 11, 2012

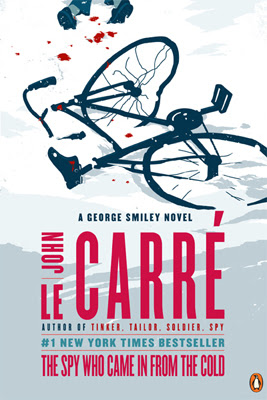

Book Review: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963)

Book Review: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold by John le Carré (1963)

John le Carré was still working for MI6 when he wrote his first two novels, Call for the Dead and A Murder of Quality, both of which focused on George Smiley. (You can read more about him here.) Apparently those books painted a bleak enough portrait of the British Secret Service, or “Circus,” as le Carré calls it (in the case of the former), and Britain’s class-fuelled society (mainly in the second) for le Carré’s mentor, author and fellow spook John Bingham, to disown his protégé entirely. But read today, they really don’t seem all that incendiary. It was with his third and most famous book, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, that the author would launch his all-out assault on the glamorous world of espionage as popularized in the bestselling novels of Ian Fleming. Le Carré wanted to expose the secret world of the British Secret Service as the seedy, hypocritical establishment he felt he saw around him every day. His hero, Alec Leamas, would not drive a Bentley or Aston Martin, would not be too fastidious about whether he took his martinis shaken or stirred (or even if his alcohol was mixed into a martini to begin with), and would not hold or use a license to kill. Despite being (or at least intended as being) a sort of anti-Bond, however—and despite spending a whole chapter pathetically laid up with a fever and subsisting on Bovril in a squalid Bayswater flat, Alec Leamas did share one crucial element with his rival: his world, however seedy, was breathtakingly exciting.

While The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is just as exciting as a Bond book, though, it is not as accessible. Which means, for my purposes, that it isn’t nearly as appealing to a twelve-year-old boy. I first attempted this book when I was in the midst of discovering James Bond and the spy genre at large, voraciously tearing through the works of Ian Fleming and Robert Ludlum, whose books I’d moved onto directly from the Hardy Boys. There was a copy of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold on one of my parents’ bookshelves, and I’d heard of le Carré, so I thought I might find something on par with the Bond and Bourne adventures I’d been reading. Plus, the title was intriguing! What was a spy doing out in the cold to begin with, I wondered? In answer, I probably imagined the beginning of A View to a Kill. I was in for a disappointment. John le Carré is really not the stuff for pre-teens. I was bored out of my mind. That bit where Leamas is laid up, sipping beef tea? It's a whole chapter! Did I mention that? And in the first half of the book, the hero spends more time working in a library and picking fights with local grocers than he does spying. You simply couldn’t go from James Bond fighting a giant squid in Doctor No to Alec Leamas doing time in prison to establish his cover. I was bored out of my mind, and I never finished the book. My first encounter with John le Carré had come at entirely the wrong time in my life. And at that point, I couldn't guess that, though the author would be absolutely loathe to admit it, le Carré's book had more in common with Fleming's than I could grasp.

Years later, however, I was spy-mad once more, and as luck would have it, I was also in a long-distance relationship, which afforded me lots of reading time on flights between Los Angeles and Chicago. And I was determined to give le Carré another chance. This time, I was an adult, I’d been exposed to far more spy literature and far more life, and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was just the thing. This time, I could get excited by spymaster Control’s ingeniously twisty, Machiavellian plan, and even by the previously boring mundanity of Leamas’s day-to-day existence as he plunges into drink and disrepair in order to make himself a tempting target for foreign agents to attempt to turn. If le Carré set out to paint the bleak reality of spying as boring and mundane compared to the sensational exploits of 007, then he succeeded… for schoolboys. But not for adults, I’m afraid, most of whom (at least those who are likewise inclined) probably find the novel as thrilling as I do. However, I don’t think that was his plan. Despite his rants against James Bond in the press at the time, I think le Carré always set out to tell a story just as exciting as Ian Fleming’s, to entertain his readers just as much. He simply uses different tools, paints with a different palette, to achieve the same effect. And though he may not have seen it at the time, there’s clearly room in the wider spy genre for both styles.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold opens with a fiftyish British spy named Alec Leamas waiting at West Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie for the only surviving agent in his network to cross over from the East. Instead, he sees him gunned down at the border. That’s the end of his network and the end of his career. He’s finished. All thanks to a ruthless East German counterspy named Hans-Dieter Mundt—the very same Mundt who slipped through George Smiley’s fingers in London in Call for the Dead. Leamas returns to the Circus in disgrace, burning with hatred for his enemy. Control (as the head of le Carré’s secret service is known) sees an opportunity to channel that hatred, and he recruits Leamas in a private long-game operation targeting Mundt directly—designed to leave him discredited and dead. I’m hesitant to describe too many details of the mission here, because part of the thrill of the book comes from the stinginess with which the author doles them out. (Honestly, le Carré uses this lack of information—playing on our desire to learn it—to the same effect that Fleming uses shootouts and encounters with deadly animals. The results are equally thrilling.) We’re at first led to believe that Leamas really is going to seed, though seasoned spy readers will see through that ploy pretty quickly. But other than realizing that the disgruntled British agent is being made over as a likely candidate for Soviet or East German recruitment, we’re never certain quite where this is going. Nor are we certain if Leamas is certain. But it’s quite a ride to watch it all unfold.

The earlier chapters are dedicated to Leamas’ squalid new (apparently) post-Circus life. Fired from the institution to which he’s dedicated his life (supposedly for stealing from the till), he drinks a lot and moves into a run-down flat. After trying a few jobs and rejecting them, he finally finds one he likes alright shelving esoteric books at a highly specialized library dedicated to “psychic research.” His co-workers there include the disagreeable boss Miss Crail, one of those great, unforgettable le Carré characters you love to hate, and a girl half his age named Liz Gold. Liz quickly falls in love with Leamas, and he indulges her and slowly grows to reciprocate her feelings in his own way. But he’s so reserved about his past, his future and everything that he remains a mystery to the frustrated Liz. That doesn’t stop her from nursing him back to health, though, once he’s stricken with a terrible fever.

Dying to understand what makes him tick, she asks him what he believes in, and he’s non-committal. He turns the question on her, and she says she believes in history. “Oh, Liz… oh no,” he says after a pause, “You’re not a bloody Communist?” And here we come to another similarity between le Carré and Fleming, despite le Carré’s insistence on distancing himself from 007 at every turn. Like Fleming, le Carré truly hates Communism. Since he seems to hate the mechanisms of the Capitalist Western governments just as much, this is sometimes overlooked in critical analyses of the author’s works. It’s true that he’s written some truly damning critiques of Britain and especially America and their behavior during and after the Cold War, but it would be a mistake to confuse anti-Americanism for pro-Communism. Most of le Carré’s books, including this one, demonstrate the tolls that spy games between East and West take on the human beings caught up in the middle. Individuals are frequently crushed by both sides, or destroyed in the conflict between them. But that doesn’t mean le Carré has any love for the East. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold positively drips with a prevailing hatred of the Communist system.

Leamas loves Liz despite her political affiliations, and she, like him, is mercilessly used by both sides. But le Carré’s utter contempt for every level of the Communist machine comes across strongly from scenes of Liz’s harmless but hopelessly disorganized local Party branch in the UK to scenes of an equally ineffectual yet far more dangerous Party meeting in East Germany to an East German secret tribunal right out of Orwell, whereas for the British spymaster Control, who shows little more regard for human lives than the KGB in executing his circuitous schemes, le Carré reserves a grudging but undeniable affection. While it condemns the Circus for using tactics not dissimilar to those of their enemy, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold remains a chillingly effective anti-Communist novel, which may come as a surprise to modern readers who think of le Carré as a left-leaning writer simply because he hates the right.

But is Control truly the architect of this devious, labyrinthine operation? To someone reading le Carré for the first time, it would certainly seem to, as it did to me when I read this book years ago on one of those red-eyes from Chicago. But if you’re reading his books in order, and have Call for the Dead and A Murder of Quality firmly in mind, then George Smiley’s fingerprints become unmistakable. In a column called The Smiley Files, it may seem odd that I’m getting to the paunchy and myopic but brilliant spymaster so late in the game. Unlike in the author’s first two novels, Smiley is not the protagonist of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. For all intents and purposes, in fact, he’s barely a presence in the novel. But then again… he is. Control tells Leamas early on that Smiley wants nothing to do with this operation because he finds it “distasteful.” (“He sees the necessity but he wants no part of it.”) And, given what we know about Smiley from his previous adventures, that certainly seems likely. But given what we learn about him in books to come (notably the “Karla Trilogy”), we know that Smiley isn’t above engaging in activities he finds distasteful if they’re an adequate means to an important end. To a casual reader unfamiliar with le Carré’s other works, there’s every reason to believe Control’s declaration. Such a reader would probably gloss right over the frequent, but seemingly inconsequential moments when Leamas sees “a little sad man with spectacles” or “a small, froglike figure in glasses” out of the corner of his eye or detects “the figure of a man in a raincoat, short and rather plump” who disappears into the shifting mist upon closer inspection. But Smiley devotees will recognize his presence again and again throughout the book, and will probably wonder exactly how large a role he really plays in masterminding the intricate scheme.

This is but one of several reasons that I’d recommend reading at least Call for the Dead before The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, despite the fact that Spy is the better book. Besides establishing a familiarity with George Smiley that enhances the reader’s grasp on the plot, Call for the Dead also provides an operational background on Mundt that makes the later book more rewarding. Furthermore, having read that one, readers will appreciate the call-backs and cameos from other recurring characters, like Peter Guillam.

Ultimately, though, it isn’t character cameos or the question of how involved George Smiley really is in the Leamas operation that makes The Spy Who Came in from the Cold such a compelling spy novel and, indeed, the template for half the books written in the genre after it. What makes it great reading—and absolutely essential reading for fans of the genre—is that operation itself, and the way the author slowly reveals its nature to his audience by peeling back layers. It’s a fascinating look at the actual workings of espionage and tradecraft that you certainly won’t get from James Bond. And, frankly, Control’s (or Smiley’s) scheme is far more ingenious than any operation M ever sends 007 off on. It’s this thrillingly realistic depiction of a plausible intelligence operation that earned le Carré his reputation as an expert in the field and a realistic chronicler of its practitioners. As the author himself later recalled, it wasn’t because the story was true that it bothered the real world spooks (if he were, he points out, he never would have been allowed to publish it); it was because it could be true. It was plausible. It’s this plausibility combined with a gifted storyteller’s imagination that makes it such compelling reading. Perhaps there are bicycles instead of Bentleys and Bovril instead of dry martinis, but this is still a spy story told by a writer with an imagination every bit as vivid as Ian Fleming’s—and therefore, however gritty and tawdry, still to some degree an escapist fantasy. For a truer-to-life depiction of the sorts of actual operations to which le Carré was witness in his own spy days, readers would have to wait until his next novel (also featuring Smiley in a reduced role), The Looking Glass War. And the only way to deliver that level of depressing truth, the author must have realized, was through a more satirical point of view than readers were yet accustomed to from the author of the page-turning Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

The Smiley Files

Part 1: George Smiley: An Introduction

Part 2: Movie Review: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Part 3: Book Review: Call for the Dead (1961)

Part 4: Movie Review: The Deadly Affair (1966)

Part 5: Book Review: A Murder of Quality (1962)

Part 6: Movie Review: A Murder of Quality (1991)

John le Carré was still working for MI6 when he wrote his first two novels, Call for the Dead and A Murder of Quality, both of which focused on George Smiley. (You can read more about him here.) Apparently those books painted a bleak enough portrait of the British Secret Service, or “Circus,” as le Carré calls it (in the case of the former), and Britain’s class-fuelled society (mainly in the second) for le Carré’s mentor, author and fellow spook John Bingham, to disown his protégé entirely. But read today, they really don’t seem all that incendiary. It was with his third and most famous book, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, that the author would launch his all-out assault on the glamorous world of espionage as popularized in the bestselling novels of Ian Fleming. Le Carré wanted to expose the secret world of the British Secret Service as the seedy, hypocritical establishment he felt he saw around him every day. His hero, Alec Leamas, would not drive a Bentley or Aston Martin, would not be too fastidious about whether he took his martinis shaken or stirred (or even if his alcohol was mixed into a martini to begin with), and would not hold or use a license to kill. Despite being (or at least intended as being) a sort of anti-Bond, however—and despite spending a whole chapter pathetically laid up with a fever and subsisting on Bovril in a squalid Bayswater flat, Alec Leamas did share one crucial element with his rival: his world, however seedy, was breathtakingly exciting.

While The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is just as exciting as a Bond book, though, it is not as accessible. Which means, for my purposes, that it isn’t nearly as appealing to a twelve-year-old boy. I first attempted this book when I was in the midst of discovering James Bond and the spy genre at large, voraciously tearing through the works of Ian Fleming and Robert Ludlum, whose books I’d moved onto directly from the Hardy Boys. There was a copy of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold on one of my parents’ bookshelves, and I’d heard of le Carré, so I thought I might find something on par with the Bond and Bourne adventures I’d been reading. Plus, the title was intriguing! What was a spy doing out in the cold to begin with, I wondered? In answer, I probably imagined the beginning of A View to a Kill. I was in for a disappointment. John le Carré is really not the stuff for pre-teens. I was bored out of my mind. That bit where Leamas is laid up, sipping beef tea? It's a whole chapter! Did I mention that? And in the first half of the book, the hero spends more time working in a library and picking fights with local grocers than he does spying. You simply couldn’t go from James Bond fighting a giant squid in Doctor No to Alec Leamas doing time in prison to establish his cover. I was bored out of my mind, and I never finished the book. My first encounter with John le Carré had come at entirely the wrong time in my life. And at that point, I couldn't guess that, though the author would be absolutely loathe to admit it, le Carré's book had more in common with Fleming's than I could grasp.

Years later, however, I was spy-mad once more, and as luck would have it, I was also in a long-distance relationship, which afforded me lots of reading time on flights between Los Angeles and Chicago. And I was determined to give le Carré another chance. This time, I was an adult, I’d been exposed to far more spy literature and far more life, and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was just the thing. This time, I could get excited by spymaster Control’s ingeniously twisty, Machiavellian plan, and even by the previously boring mundanity of Leamas’s day-to-day existence as he plunges into drink and disrepair in order to make himself a tempting target for foreign agents to attempt to turn. If le Carré set out to paint the bleak reality of spying as boring and mundane compared to the sensational exploits of 007, then he succeeded… for schoolboys. But not for adults, I’m afraid, most of whom (at least those who are likewise inclined) probably find the novel as thrilling as I do. However, I don’t think that was his plan. Despite his rants against James Bond in the press at the time, I think le Carré always set out to tell a story just as exciting as Ian Fleming’s, to entertain his readers just as much. He simply uses different tools, paints with a different palette, to achieve the same effect. And though he may not have seen it at the time, there’s clearly room in the wider spy genre for both styles.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold opens with a fiftyish British spy named Alec Leamas waiting at West Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie for the only surviving agent in his network to cross over from the East. Instead, he sees him gunned down at the border. That’s the end of his network and the end of his career. He’s finished. All thanks to a ruthless East German counterspy named Hans-Dieter Mundt—the very same Mundt who slipped through George Smiley’s fingers in London in Call for the Dead. Leamas returns to the Circus in disgrace, burning with hatred for his enemy. Control (as the head of le Carré’s secret service is known) sees an opportunity to channel that hatred, and he recruits Leamas in a private long-game operation targeting Mundt directly—designed to leave him discredited and dead. I’m hesitant to describe too many details of the mission here, because part of the thrill of the book comes from the stinginess with which the author doles them out. (Honestly, le Carré uses this lack of information—playing on our desire to learn it—to the same effect that Fleming uses shootouts and encounters with deadly animals. The results are equally thrilling.) We’re at first led to believe that Leamas really is going to seed, though seasoned spy readers will see through that ploy pretty quickly. But other than realizing that the disgruntled British agent is being made over as a likely candidate for Soviet or East German recruitment, we’re never certain quite where this is going. Nor are we certain if Leamas is certain. But it’s quite a ride to watch it all unfold.

The earlier chapters are dedicated to Leamas’ squalid new (apparently) post-Circus life. Fired from the institution to which he’s dedicated his life (supposedly for stealing from the till), he drinks a lot and moves into a run-down flat. After trying a few jobs and rejecting them, he finally finds one he likes alright shelving esoteric books at a highly specialized library dedicated to “psychic research.” His co-workers there include the disagreeable boss Miss Crail, one of those great, unforgettable le Carré characters you love to hate, and a girl half his age named Liz Gold. Liz quickly falls in love with Leamas, and he indulges her and slowly grows to reciprocate her feelings in his own way. But he’s so reserved about his past, his future and everything that he remains a mystery to the frustrated Liz. That doesn’t stop her from nursing him back to health, though, once he’s stricken with a terrible fever.

Dying to understand what makes him tick, she asks him what he believes in, and he’s non-committal. He turns the question on her, and she says she believes in history. “Oh, Liz… oh no,” he says after a pause, “You’re not a bloody Communist?” And here we come to another similarity between le Carré and Fleming, despite le Carré’s insistence on distancing himself from 007 at every turn. Like Fleming, le Carré truly hates Communism. Since he seems to hate the mechanisms of the Capitalist Western governments just as much, this is sometimes overlooked in critical analyses of the author’s works. It’s true that he’s written some truly damning critiques of Britain and especially America and their behavior during and after the Cold War, but it would be a mistake to confuse anti-Americanism for pro-Communism. Most of le Carré’s books, including this one, demonstrate the tolls that spy games between East and West take on the human beings caught up in the middle. Individuals are frequently crushed by both sides, or destroyed in the conflict between them. But that doesn’t mean le Carré has any love for the East. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold positively drips with a prevailing hatred of the Communist system.

Leamas loves Liz despite her political affiliations, and she, like him, is mercilessly used by both sides. But le Carré’s utter contempt for every level of the Communist machine comes across strongly from scenes of Liz’s harmless but hopelessly disorganized local Party branch in the UK to scenes of an equally ineffectual yet far more dangerous Party meeting in East Germany to an East German secret tribunal right out of Orwell, whereas for the British spymaster Control, who shows little more regard for human lives than the KGB in executing his circuitous schemes, le Carré reserves a grudging but undeniable affection. While it condemns the Circus for using tactics not dissimilar to those of their enemy, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold remains a chillingly effective anti-Communist novel, which may come as a surprise to modern readers who think of le Carré as a left-leaning writer simply because he hates the right.

But is Control truly the architect of this devious, labyrinthine operation? To someone reading le Carré for the first time, it would certainly seem to, as it did to me when I read this book years ago on one of those red-eyes from Chicago. But if you’re reading his books in order, and have Call for the Dead and A Murder of Quality firmly in mind, then George Smiley’s fingerprints become unmistakable. In a column called The Smiley Files, it may seem odd that I’m getting to the paunchy and myopic but brilliant spymaster so late in the game. Unlike in the author’s first two novels, Smiley is not the protagonist of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. For all intents and purposes, in fact, he’s barely a presence in the novel. But then again… he is. Control tells Leamas early on that Smiley wants nothing to do with this operation because he finds it “distasteful.” (“He sees the necessity but he wants no part of it.”) And, given what we know about Smiley from his previous adventures, that certainly seems likely. But given what we learn about him in books to come (notably the “Karla Trilogy”), we know that Smiley isn’t above engaging in activities he finds distasteful if they’re an adequate means to an important end. To a casual reader unfamiliar with le Carré’s other works, there’s every reason to believe Control’s declaration. Such a reader would probably gloss right over the frequent, but seemingly inconsequential moments when Leamas sees “a little sad man with spectacles” or “a small, froglike figure in glasses” out of the corner of his eye or detects “the figure of a man in a raincoat, short and rather plump” who disappears into the shifting mist upon closer inspection. But Smiley devotees will recognize his presence again and again throughout the book, and will probably wonder exactly how large a role he really plays in masterminding the intricate scheme.

This is but one of several reasons that I’d recommend reading at least Call for the Dead before The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, despite the fact that Spy is the better book. Besides establishing a familiarity with George Smiley that enhances the reader’s grasp on the plot, Call for the Dead also provides an operational background on Mundt that makes the later book more rewarding. Furthermore, having read that one, readers will appreciate the call-backs and cameos from other recurring characters, like Peter Guillam.

Ultimately, though, it isn’t character cameos or the question of how involved George Smiley really is in the Leamas operation that makes The Spy Who Came in from the Cold such a compelling spy novel and, indeed, the template for half the books written in the genre after it. What makes it great reading—and absolutely essential reading for fans of the genre—is that operation itself, and the way the author slowly reveals its nature to his audience by peeling back layers. It’s a fascinating look at the actual workings of espionage and tradecraft that you certainly won’t get from James Bond. And, frankly, Control’s (or Smiley’s) scheme is far more ingenious than any operation M ever sends 007 off on. It’s this thrillingly realistic depiction of a plausible intelligence operation that earned le Carré his reputation as an expert in the field and a realistic chronicler of its practitioners. As the author himself later recalled, it wasn’t because the story was true that it bothered the real world spooks (if he were, he points out, he never would have been allowed to publish it); it was because it could be true. It was plausible. It’s this plausibility combined with a gifted storyteller’s imagination that makes it such compelling reading. Perhaps there are bicycles instead of Bentleys and Bovril instead of dry martinis, but this is still a spy story told by a writer with an imagination every bit as vivid as Ian Fleming’s—and therefore, however gritty and tawdry, still to some degree an escapist fantasy. For a truer-to-life depiction of the sorts of actual operations to which le Carré was witness in his own spy days, readers would have to wait until his next novel (also featuring Smiley in a reduced role), The Looking Glass War. And the only way to deliver that level of depressing truth, the author must have realized, was through a more satirical point of view than readers were yet accustomed to from the author of the page-turning Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

The Smiley Files

Part 1: George Smiley: An Introduction

Part 2: Movie Review: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Part 3: Book Review: Call for the Dead (1961)

Part 4: Movie Review: The Deadly Affair (1966)

Part 5: Book Review: A Murder of Quality (1962)

Part 6: Movie Review: A Murder of Quality (1991)

More Skyfall Stills Appear in French Magazine

French magazine Studio Ciné Live has published some very cool looking new stills from Skyfall, and scans like this one have turned up in the MI6 community forums, on Bond23.net (via MI6) and other sites. With a teaser trailer rumored to appear in May, we'll probably start seeing a lot more images from the new James Bond movie in the months ahead!

Upcoming Spy DVDs: Lancelot Link, Secret Chimp Complete Collector's Edition

I was excited when a link for this first turned up on Amazon a few months ago, but then it disappeared. Now TV Shows On DVD reports that a Lancelot Link, Secret Chimp Complete Collector's Edition is due out May 29 from Film Chest! A previous release on Image was incomplete and basically bootleg quality, but even so those out of print discs command high prices on the resale market. Not anymore, thanks to this new release, since this one supersedes the old one in all respects. Film Chest's 3-disc Collector's Edition contains all of the Saturday morning ABC show's 17 episodes (each of which actually featured two separate 15-minute adventures) transferred from the original ABC vault masters (rather than dubbed from off-air VHS recordings), plus bonus content like the music and videos of the all monkey band Evolution Revolution, whose segments were introduced on the original series by ape talk show host "Ed Simian."

Perhaps I should backtrack in case there's anyone here unfamiliar with Lancelot Link. As you'd probably deduce from that cover art, Lancelot Link was a chimpanzee secret agent. He worked for the secret organization APE (Agency to Prevent Evil) and tangled with the nefarious agents of CHUMP (Criminal Headquarters for Underworld Master Plan). All characters were played by trained primates and voiced by human comedians. Such a concoction could only have arisen from the spy-mad Sixties (indeed, Lancelot Link might be the ultimate product of the secret agent mania spawned by James Bond which trickled down to all facets of the media), but Lancelot Link, Secret Chimp didn't actually hit airwaves until 1970. (It ran until '72.) Your enjoyment of the series will no doubt be predicated upon your personal tolerance for languidly paced human-voiced monkey antics with jokes recycled from Get Smart, and you're probably better qualified to judge that for yourself than I can. But for a certain breed of spy fan, this release is sure to be most welcome! Retail is a modest $24.98, but of course it's bound to be less on Amazon.

Perhaps I should backtrack in case there's anyone here unfamiliar with Lancelot Link. As you'd probably deduce from that cover art, Lancelot Link was a chimpanzee secret agent. He worked for the secret organization APE (Agency to Prevent Evil) and tangled with the nefarious agents of CHUMP (Criminal Headquarters for Underworld Master Plan). All characters were played by trained primates and voiced by human comedians. Such a concoction could only have arisen from the spy-mad Sixties (indeed, Lancelot Link might be the ultimate product of the secret agent mania spawned by James Bond which trickled down to all facets of the media), but Lancelot Link, Secret Chimp didn't actually hit airwaves until 1970. (It ran until '72.) Your enjoyment of the series will no doubt be predicated upon your personal tolerance for languidly paced human-voiced monkey antics with jokes recycled from Get Smart, and you're probably better qualified to judge that for yourself than I can. But for a certain breed of spy fan, this release is sure to be most welcome! Retail is a modest $24.98, but of course it's bound to be less on Amazon.

Apr 9, 2012

The Spies of Avengers Assemble Get Their Own Posters

Yeah, it's once again time to talk about the big Marvel superhero movie that's also chock-full of spies coming out next month. But so I don't have to keep doing my whole elaborate explanation of how it's not the Avengers that we all know and love, I'm going to use the UK title from now on when discussing Joss Whedon's Avengers Assemble. Disney realized at the last minute (after already spending a fortune on a campaign based around the U.S. title) that most viewers in the UK still associate the title "The Avengers" with some old TV show from the Sixties. Who woulda thought? Stupid Disney. It still irks me that Marvel stole the title from the greatest spy series ever to begin with, but now that I can call it Avengers Assemble (which is honestly a better title anyway), I'm less irked and can focus more on being excited that there's actually a huge budget movie about Marvel's superspies, including agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Nick Fury, Black Widow, Maria Hill and Hawkeye. Sure, there are also some better known superheroes in the mix (Iron Man, Captain America, Thor and the Hulk), but the thing I'm most excited about is the spies. And as seen in the Japanese trailer and the latest TV spot (below), director Joss Whedon has even included the improbable but awesome S.H.I.E.L.D. Helicarrier, right out of those classic Sixties Steranko comics! All those S.H.I.E.L.D. agents get their own posters, too--even fan favorite Agent Coulson (Clark Gregg), a character created especially for the movies (though very similar to the comics' Jasper Sitwell) who's developed his own cult following. Here, courtesy of the IMP Awards (via Dark Horizons) are some movie posters featuring Coulson, Nick Fury (Samuel L. Jackson), Black Widow (Scarlett Johanssen) and Maria Hill (Coby Smulders). Hey, I didn't say they were good posters... but they do show the spies.

Tradecraft: Reelz Picks Up XIII Series

I could have sworn that I'd already reported on the new EuropaCorp-produced TV series version of Jean Van Hamme's Bourne-inspired XIII graphic novels, but if I did, I can't find the post. Anyway, Luc Besson's production company (the people behind such neo-Eurospy movies as Taken, From Paris With Love and the Transporter trilogy) previously produced a XIII miniseries starring Stephen Dorff and Val Kilmer (released on DVD and Blu-ray as XIII: The Conspiracy), and now they've produced a whole TV show based on the concept. This time Stuart Townsend stars as the amnesiac secret agent known only as "XIII," and Archer's Aisha Tyler co-stars playing a live action spy instead of an animated one. Bond Girl Caterina Murino (who also appeared in the miniseries) has a recurring role. Today, Deadline reports that the ReelzChannel (which is really a thing, apparently; I think it's a cable network) has picked it up for U.S. broadcast. XIII will premiere in June on ReelzChannel. One 13-episode season has already aired in Europe and Canada, with another set for broadcast sometime this year.

Apr 3, 2012

Tradecraft: When the Nemesis Becomes the Hunted (and She's Still Melissa George)

The Melissa George spy series formerly known as Nemesis and even more formerly known as Morton is now known as Hunted, according to The Hollywood Reporter. (Note to producers: of those three options, the correct title is Nemesis. Please go back to that. Thank you.) Hunted is created and written by Frank Spotnitz (Strike Back, The X-Files) and directed by S.J. Clarkson (Hustle). The trade recaps what we (mostly) already knew about the plot thusly: "George [Alias] plays Sam, a spy who has just escaped an assassination attempt by a member of her own team and goes back to work undercover as a nanny, not knowing who tried to kill her or who to trust." Spotnitz has been experimenting with the European TV production model, and collaborated with UK production company Kudos (MI-5) on Hunted, shooting on location in London, Scotland and Morocco. “The showrunner model works very well in the US,” Spotnitz told the crowd at the MIPTV conference in Cannes, “but it’s a different creative culture [in Europe]. I’ve been trying to take the best of both worlds and I’m still in process of figuring out how to do that.” One thing he's taken from the UK world is a short season. The trade reports that "the first season will follow the same storyline over eight hours, and Spotnitz and his team are already thinking about upcoming seasons and different locations, though nothing has been confirmed just yet." Hunted will air this fall on BBC1 in the UK and Cinemax in the U.S.