In a great profile in Saturday's New York Times promoting his new novel Agent Running in the Field, author John le Carré reveals that his sons' production company, The Ink Factory, are plotting an epic new TV series about his most famous character, spymaster George Smiley. "According to le Carré," asserts the article's author, Tobias Grey, "The Ink Factory now plans to do new television adaptations of all the novels featuring Cold War spy George Smiley - this time in chronological order. 'That means that if you actually go back to the first big conspiracies in The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, you've got to consider how Smiley ages and how young he was at that time,' le Carré says. That would mean finding an actor who can play younger than the Smiley incarnated by Gary Oldman in the film version of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. Le Carré says that his sons are interested in casting the British actor Jared Harris, whose performance they all admired in the recent TV mini-series Chernobyl." Harris (The Man From U.N.C.L.E., Allied), interestingly, was originally cast in Tomas Alfredson's 2011 le Carré adaptation Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy as Circus (MI6) chief Percy Alleline, but had to drop out due to scheduling conflicts with Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, in which he played Professor Moriarty. Toby Jones took on the Alleline role, and embodied the character perfectly. Besides Oldman, Smiley has been played in the past by Denholm Elliott, James Mason, Rupert Davies, and, most memorably, Alec Guinness in two famous BBC miniseries.

A new miniseries version of The Spy Who Came In From the Cold was first announced back in 2016 as a follow-up to the hugely successful le Carré miniseries The Night Manager. Le Carré worked with the producers and writer to crack their take on the material, and that work led him to write a whole new sequel to the book, A Legacy of Spies, but did not yield a series. Instead, The Little Drummer Girl (2018) proved to be the next le Carré miniseries, but work continued on The Spy Who Came In From the Cold. Now, apparently, that project has grown in scope and morphed into this one. I've long craved a long-form TV series about le Carré's Circus, devoting a season to each book and dropping in the short stories from The Secret Pilgrim at the appropriate historical moments and, most crucially, finally giving us a television version of the (to date unfilmed) middle book in the Karla trilogy, The Honourable Schoolboy. This sounds like it could turn out to be exactly that! (Though hopefully they'll begin at the real beginning with Call For the Dead, and not The Spy Who Came In From the Cold.) It's a most tantalizing prospect!

Read my George Smiley Primer here.

Showing posts with label Smiley. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Smiley. Show all posts

Oct 13, 2019

Sep 19, 2017

Discussing A LEGACY OF SPIES on the Spybrary Podcast

On the latest episode of the Spybrary Podcast, I join host Shane Whaley and Spywrite's Jeff Quest to discuss John le Carré's brand new Smiley novel, A Legacy of Spies. At the beginning of the summer, Shane and I discussed the first Smiley novel, Call for the Dead, so it feels appropriate to end the summer discussing the latest one! Furthermore, Jeff and I have been trying to do a podcast together for a few years now, so I'm really happy that Shane finally made that happen. I will be posting a full review here of A Legacy of Spies later, but in the meantime, listen to the podcast to hear my feelings on the book.

Listen to Episode 18 of The Spybrary Podcast (A Legacy of Spies) here, or subscribe on iTunes.

Listen to Episode 006 of The Spybrary Podcast (Call for the Dead) here,

Read "George Smiley: An Introduction" here.

Purchase A Legacy of Spies on Amazon.

Listen to Episode 18 of The Spybrary Podcast (A Legacy of Spies) here, or subscribe on iTunes.

Listen to Episode 006 of The Spybrary Podcast (Call for the Dead) here,

Read "George Smiley: An Introduction" here.

Purchase A Legacy of Spies on Amazon.

Sep 14, 2017

John le Carré's DEADLY AFFAIR Comes to Blu-Ray in Fabulous Special Edition

Amidst the flurry of John le Carré excitement surrounding the publication of the great author's new Smiley novel, A Legacy of Spies, an excellent new Blu-ray release of the film of his first book has gone somewhat overlooked. Sidney Lumet's The Deadly Affair (1966) was adapted from le Carré's debut novel Call for the Dead, and starred James Mason as the hero readers knew as George Smiley, here rechristened "Charles Dobbs" because Paramount owned the rights to Smiley following their film of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold the previous year (in which the character only had a small part). That film's screenwriter, Paul Dehn (who also adapted Goldfinger for the screen) also penned the script for The Deadly Affair... and actually managed to make a few improvements on the book! Mason is terrific as Dobbs, and sadly overlooked when we think of screen Smileys thanks to his more famous successors. In my opinion, The Deadly Affair is the most underrated of the films of le Carré's oeuvre. (Read my review of it here.) As such, its home video track record has been a bit spotty. For years it was available only as a rather unimpressive Region 2 DVD, and when it finally got Region 1 attention it was merely as a sparse, featureless MOD title from Sony's Columbia Screen Classics by Request. Now that oversight has finally been redressed, thanks to UK company Indicator, who have released a truly impressive, special feature-laden, region-free, limited edition Blu-ray/DVD combo! And the transfer is even more impressive than the supplements. This movie has never looked so good, and takes on a whole new life in Indicator's high-def remaster. Here's a rundown of the set's features:

Amidst the flurry of John le Carré excitement surrounding the publication of the great author's new Smiley novel, A Legacy of Spies, an excellent new Blu-ray release of the film of his first book has gone somewhat overlooked. Sidney Lumet's The Deadly Affair (1966) was adapted from le Carré's debut novel Call for the Dead, and starred James Mason as the hero readers knew as George Smiley, here rechristened "Charles Dobbs" because Paramount owned the rights to Smiley following their film of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold the previous year (in which the character only had a small part). That film's screenwriter, Paul Dehn (who also adapted Goldfinger for the screen) also penned the script for The Deadly Affair... and actually managed to make a few improvements on the book! Mason is terrific as Dobbs, and sadly overlooked when we think of screen Smileys thanks to his more famous successors. In my opinion, The Deadly Affair is the most underrated of the films of le Carré's oeuvre. (Read my review of it here.) As such, its home video track record has been a bit spotty. For years it was available only as a rather unimpressive Region 2 DVD, and when it finally got Region 1 attention it was merely as a sparse, featureless MOD title from Sony's Columbia Screen Classics by Request. Now that oversight has finally been redressed, thanks to UK company Indicator, who have released a truly impressive, special feature-laden, region-free, limited edition Blu-ray/DVD combo! And the transfer is even more impressive than the supplements. This movie has never looked so good, and takes on a whole new life in Indicator's high-def remaster. Here's a rundown of the set's features:

• High Definition remaster

• Original mono audio

• Audio commentary with film historians Michael Brooke and Johnny Mains

• The National Film Theatre Lecture with James Mason (1967, 48 mins): archival audio recording of an interview conducted by Leslie Hardcastle at the National Film Theatre, London

• The Guardian Lecture with Sidney Lumet (1983, 89 mins): archival audio recording of an interview conducted by Derek Malcolm at the National Film Theatre, London

• A Different Kind of Spy: Paul Dehn's Deadly Affair (2017, 17 mins): writer David Kipen on screenwriter Paul Dehn

• New interview with camera operator Brian West (2017, 5 mins)

• New interview with camera operator Brian West (2017, 5 mins)

• Original theatrical trailer

• Image gallery: on-set and promotional photography

• New English subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing

• Limited edition exclusive booklet featuring newly commissioned writing by Thirza Wakefield , an overview of contemporary critical responses, and historic articles on the film including interviews with James Mason and cinematographer Freddie Young

It also features a cool reversible cover with two choices of poster art and a choice of dark or light spines, either one of which will look good on the shelf next to your Criterion Spy Who Came in from the Cold Blu-ray. The Blu-ray world premiere of The Deadly Affair, a dual format edition, is strictly limited to 3,000 copies; any future pressings, should they happen, won't include the excellent 48-page booklet. (And trust me, you want this booklet!)

The features are excellent, though Kipen misspeaks a couple of times. After reiterating le Carré's claim from his interview on the Criterion Spy Who Came in from the Cold disc that screenwriter Dehn was an assassin for the SOE during WWII, he implies that le Carré trained under Dehn at Camp X with Ian Fleming and Christopher Lee. (Le Carré didn't sign up for spook school until well after the war.) And later he implies that Dehn wrote more than one of the early James Bond movies. It really should have been up to the producers of the special features to edit him better; I get the impression these are just conversational blunders and I suspect he instantly regretted them, as overall he comes across as quite knowledgeable. And despite those minor hiccups, it's great to finally have a documentary shining the spotlight on the underrated Dehn! I learned a lot from this piece, including the fascinating tidbit that Dehn's longtime partner was Hammer composer James Bernard. For some reason Kipen doesn't tell us why Smiley was changed to Dobbs, but this crucial bit of information is covered in depth on the commentary track. He does talk about some of Dehn's earlier, more obscure spy movies, which is great to see. West relates some very interesting anecdotes about cinematographer Freddie Young, and ably gives a great example of just what exactly camera operators and cinematographers do in the form of an amusing anecdote about shooting the scene in theater with Lynn Redgrave. Basically, all of the features are terrific, the transfer looks great, and this is a disc that all le Carré fans and all Sixties spy fans simply need! The region-free disc should be playable everywhere and can be ordered from Amazon.com or Amazon UK. (American consumers may find it works out in their favor to order from the UK.)

Jun 6, 2017

Talking le Carré on the Spybrary Podcast

I'm a guest on the latest episode of the Spybrary Podcast, where host Shane Whaley and I discuss John le Carré's debut novel, Call for the Dead. Call for the Dead was also the debut of one of the greatest characters in spy fiction, George Smiley, whose more famous outings include Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. We also touch on the 1966 film version, The Deadly Affair, which was adapted by Paul Dehn in the same remarkable three-year period in which he also penned Goldfinger and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. It was a pleasure talking spy fiction with Shane, and I hope to do so again in the future.

Listen to Episode 006 of The Spybrary Podcast here, or subscribe on iTunes.

Read "George Smiley: An Introduction" here.

Read my review of Call for the Dead here.

Read my review of The Deadly Affair here.

Purchase Call for the Dead on Amazon.

Purchase The Deadly Affair on Amazon.

Listen to Episode 006 of The Spybrary Podcast here, or subscribe on iTunes.

Read "George Smiley: An Introduction" here.

Read my review of Call for the Dead here.

Read my review of The Deadly Affair here.

Purchase Call for the Dead on Amazon.

Purchase The Deadly Affair on Amazon.

Mar 7, 2017

John le Carré to Publish New George Smiley Novel A Legacy of Spies!

This is perhaps the most exciting news I have ever written about here, in my ten plus years of blogging about fictional spies. It was announced today that John le Carré, the master of the espionage genre (and my personal favorite writer of all time) will publish a new novel about his most famous protagonist, George Smiley, in the fall. A new Smiley novel! Can it possibly be true? It is! There's a plot description on the author's website and even a pre-order listing on Amazon. A Legacy of Spies will be published September 5, 2017, in the United States, and September 7 in Britain. Here is the official description:

Le Carré has always prided himself on staying topical and never looking" back, never dwelling on the past. When the Berlin Wall came down, many critics tried to write him off, but he not only stayed aggressively relevant in the post-Cold War world; he produced some of his greatest work against the backdrop of the New World Order (The Night Manager, Our Game) and the War on Terror (A Most Wanted Man). Perhaps writing his memoirs, The Pigeon Tunnel (published last year) got him in a more reflective mood and inspired him to revisit his beloved Cold War characters, but it certainly sounds like he's found a way to do so while still remaining doggedly current, which seems appropriate, especially in a time when half the daily headlines seem torn from the pages of a le Carré novel!

George Smiley first appeared as the protagonist of le Carré's first novel, Call for the Dead (1961), and served the same role in his second, A Murder of Quality (1962). The character took a backseat in his next two books, playing a more minor role in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) and The Looking Glass War (1965), before taking center stage once more in the epic "Quest for Karla" trilogy, beginning with Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974), and continuing with The Honourable Schoolboy (1977) and Smiley's People (1979). Just as the character never seemed to be able to retire from "the Circus" (as British Intelligence is known in le Carré jargon), the author never seemed quite ready to retire his character. He brought George back (again relegated to a secondary role) for a swan song in The Secret Pilgrim (1990), his eulogy for the Cold War. "It's over, and so am I. Absolutely over," Smiley told a gathering of MI6's latest recruits. "Time you rang down the curtain on yesterday's cold warrior... The new time needs new people. The worst thing you can do is imitate us." And so he exits, leaving them with one final piece of advice: "We've given up far too many freedoms in order to be free. Now we've got to take them back." Even that exit, it now seems, was not, absolutely, his final. I suspect the new novel will develop that final theme further.

Two other le Carré novels, The Russia House (1989) and The Night Manager (1993) are set in the same world and feature some of the same characters, but not Smiley himself. They form a loose trilogy with The Secret Pilgrim as the middle book. The latter, which was made into a successful miniseries last year, features Smiley's Secret Service protege, Burr.

Smiley himself has been portrayed many times on screen, most famously by Alec Guinness in a pair of BBC miniseries and most recently by Gary Oldman in Tomas Alfredson's 2011 feature film adaptation of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Presumably, he'll next be seen on the small screen in the forthcoming miniseries version of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (previously filmed in 1965).

The Smiley Files

Part 1: George Smiley: An Introduction

Part 2: Movie Review: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Part 3: Book Review: Call for the Dead (1961)

Part 4: Movie Review: The Deadly Affair (1966)

Part 5: Book Review: A Murder of Quality (1962)

Part 6: Movie Review: A Murder of Quality (1991)

Part 7: Book Review: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963)

Part 8: Book Review: The Looking Glass War (1965)

Part 9: Book Review: Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974)

After 25 years, Smiley is back...

Peter Guillam, staunch colleague and disciple of George Smiley of the British Secret Service, otherwise known as the Circus, is living out his old age on the family farmstead on the south coast of Brittany when a letter from his old Service summons him to London. The reason? His Cold War past has come back to claim him.

Intelligence operations that were once the toast of secret London, and involved such characters as Alec Leamas, Jim Prideaux, George Smiley and Peter Guillam himself, are to be scrutinised under disturbing criteria by a generation with no memory of the Cold War and no patience with its justifications.

Interweaving past with present so that each may tell its own intense story, John le Carré has spun a single plot as ingenious and thrilling as the two predecessors on which it looks back: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.So not just Smiley will be back, but also many of our other favorite characters from the earlier novels, including Guillam (whose role was disappointingly small in the previously final Smiley outing, The Secret Pilgrim) and even Alec Leamas, hero of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold! (Le Carré once seemed sworn against ever writing about him again, joking in his introduction to a later edition of The Looking Glass War that at the time of its initial publication, all the UK public seemed to want from him was Alec Leamas Rides Again.) Penguin editor Mary Mount provides some further fascinating hints of what we can expect from A Legacy of Spies on the Penguin website. "A Legacy of Spies asks questions about how we reckon with the past and with our political history," she writes. "As with all of le Carré’s fiction, it brilliantly illuminates human folly and our frailty. The pain, the clarity, of hindsight is so beautifully rendered showing how the passage of time fully exposes acts of violence, framed as utterly necessary at the time, for what they are."

Le Carré has always prided himself on staying topical and never looking" back, never dwelling on the past. When the Berlin Wall came down, many critics tried to write him off, but he not only stayed aggressively relevant in the post-Cold War world; he produced some of his greatest work against the backdrop of the New World Order (The Night Manager, Our Game) and the War on Terror (A Most Wanted Man). Perhaps writing his memoirs, The Pigeon Tunnel (published last year) got him in a more reflective mood and inspired him to revisit his beloved Cold War characters, but it certainly sounds like he's found a way to do so while still remaining doggedly current, which seems appropriate, especially in a time when half the daily headlines seem torn from the pages of a le Carré novel!

George Smiley first appeared as the protagonist of le Carré's first novel, Call for the Dead (1961), and served the same role in his second, A Murder of Quality (1962). The character took a backseat in his next two books, playing a more minor role in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) and The Looking Glass War (1965), before taking center stage once more in the epic "Quest for Karla" trilogy, beginning with Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974), and continuing with The Honourable Schoolboy (1977) and Smiley's People (1979). Just as the character never seemed to be able to retire from "the Circus" (as British Intelligence is known in le Carré jargon), the author never seemed quite ready to retire his character. He brought George back (again relegated to a secondary role) for a swan song in The Secret Pilgrim (1990), his eulogy for the Cold War. "It's over, and so am I. Absolutely over," Smiley told a gathering of MI6's latest recruits. "Time you rang down the curtain on yesterday's cold warrior... The new time needs new people. The worst thing you can do is imitate us." And so he exits, leaving them with one final piece of advice: "We've given up far too many freedoms in order to be free. Now we've got to take them back." Even that exit, it now seems, was not, absolutely, his final. I suspect the new novel will develop that final theme further.

Two other le Carré novels, The Russia House (1989) and The Night Manager (1993) are set in the same world and feature some of the same characters, but not Smiley himself. They form a loose trilogy with The Secret Pilgrim as the middle book. The latter, which was made into a successful miniseries last year, features Smiley's Secret Service protege, Burr.

Smiley himself has been portrayed many times on screen, most famously by Alec Guinness in a pair of BBC miniseries and most recently by Gary Oldman in Tomas Alfredson's 2011 feature film adaptation of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Presumably, he'll next be seen on the small screen in the forthcoming miniseries version of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (previously filmed in 1965).

The Smiley Files

Part 1: George Smiley: An Introduction

Part 2: Movie Review: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Part 3: Book Review: Call for the Dead (1961)

Part 4: Movie Review: The Deadly Affair (1966)

Part 5: Book Review: A Murder of Quality (1962)

Part 6: Movie Review: A Murder of Quality (1991)

Part 7: Book Review: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963)

Part 8: Book Review: The Looking Glass War (1965)

Part 9: Book Review: Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974)

Jul 20, 2016

Tradecraft: Smiley Returns to the Small Screen in New The Spy Who Came in from the Cold Miniseries

In an introduction to a paperback edition of The Looking Glass War, John le Carré joked that what the public wanted from him at the time he wrote that book was "Alec Leamas Rides Again." Unlikely as that prospect seemed, it looks like Leamas, the titular Spy Who Came in from the Cold, will indeed ride again! This is certainly exciting news. The success of The Night Manager miniseries (or "limited series," to use the preferred term du jour) in both Britain and America guaranteed we'd be seeing more le Carré adaptations on the small screen, but I honestly didn't expect a new version of what's probably his most famous novel (and one of the best spy novels of all time). Yet that is in the works! Deadline reports that Paramount TV and The Ink Factory (the production shingle run by le Carré's sons with a mandate to develop film and television projects based on his works) are developing the property as a limited series with Simon Beaufoy (Slumdog Millionaire, The Hunger Games: Catching Fire) writing. Le Carré will serve as executive producer, as he did on The Night Manager. No network is involved at this stage, though one has to imagine that both of Night Manager's partners, the BBC (in Britain) and AMC (in the United States), will bid hard for a follow-up of this magnitude.

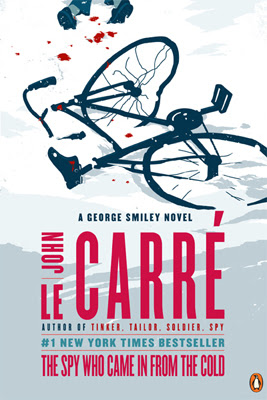

Though it was his third novel (and also third featuring George Smiley), it was The Spy Who Came in from the Cold that put le Carré on the map. Upon its publication in 1963, the book garnered excellent reviews and became a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. Martin Ritt made an excellent film of it in 1965 starring Richard Burton and Claire Bloom and co-written by Goldfinger scribe Paul Dehn. But as good as that film is, I don't see it as the last word on the story. In fact, I've long harbored dreams of a Spy Who Came in from the Cold remake. Making it in a new format (as a miniseries) will afford Beaufoy the opportunity to make different choices from Ritt and Dehn, and to flesh out certain aspects of le Carré's novel that got short shrift in the film, just as the Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy feature proved a fresh take on that material from the famous BBC miniseries that came before.

No casting has been announced, and it is probably a long way off at this stage. But I would guess that, like The Night Manager, this title will attract high caliber stars. Personally, my dream cast for a Spy Who Came in from the Cold remake has long been Daniel Craig as Leamas (I think he'd be perfect!) and Keira Knightly as Liz (who can now use her actual name; in the film it was changed to Nan because of Burton's famous wife named Liz). Craig, however, is committed to another TV series, and sadly unlikely to be available. Even more important, though, are the supporting roles. I really, really hope that The Ink Factory's producers Stephen Cornwell and Simon Cornwell will manage to lure their Tinker Tailor actors back in the roles of Smiley and, more crucially, Control. While it seems somewhat unlikely that Gary Oldman would want to reprise his film role on television for what basically amounts to a cameo, I have trouble picturing anyone other than John Hurt in the role of Control. He was utterly fantastic in Tinker Tailor. (Spy would be a prequel to that story, which was adapted from a later book.) And Hurt certainly does television.

The only thing I'm slightly disappointed about regarding this news is the fact that they're not doing Call for the Dead first. Though Call for the Dead (which was filmed in the Sixties as The Deadly Affair, also adapted by Dehn) features Smiley front and center and Spy does not, Spy is very much a sequel to Call. I wonder if Beaufoy will be able to incorporate certain aspects of that novel into his adaptation? Depending on how many episodes the miniseries turns out to be, that could be a very interesting approach.

What this news means for the Ink Factory's previously announced follow-up to The Night Manager, a 3-part adaptation of le Carre's 2003 novel Absolute Friends, remains to be seen. Hopefully that is still on track as well. (It may even materialize before The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.)

Read my book review of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold here.

Read my overview "George Smiley: An Introduction" here.

Though it was his third novel (and also third featuring George Smiley), it was The Spy Who Came in from the Cold that put le Carré on the map. Upon its publication in 1963, the book garnered excellent reviews and became a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. Martin Ritt made an excellent film of it in 1965 starring Richard Burton and Claire Bloom and co-written by Goldfinger scribe Paul Dehn. But as good as that film is, I don't see it as the last word on the story. In fact, I've long harbored dreams of a Spy Who Came in from the Cold remake. Making it in a new format (as a miniseries) will afford Beaufoy the opportunity to make different choices from Ritt and Dehn, and to flesh out certain aspects of le Carré's novel that got short shrift in the film, just as the Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy feature proved a fresh take on that material from the famous BBC miniseries that came before.

No casting has been announced, and it is probably a long way off at this stage. But I would guess that, like The Night Manager, this title will attract high caliber stars. Personally, my dream cast for a Spy Who Came in from the Cold remake has long been Daniel Craig as Leamas (I think he'd be perfect!) and Keira Knightly as Liz (who can now use her actual name; in the film it was changed to Nan because of Burton's famous wife named Liz). Craig, however, is committed to another TV series, and sadly unlikely to be available. Even more important, though, are the supporting roles. I really, really hope that The Ink Factory's producers Stephen Cornwell and Simon Cornwell will manage to lure their Tinker Tailor actors back in the roles of Smiley and, more crucially, Control. While it seems somewhat unlikely that Gary Oldman would want to reprise his film role on television for what basically amounts to a cameo, I have trouble picturing anyone other than John Hurt in the role of Control. He was utterly fantastic in Tinker Tailor. (Spy would be a prequel to that story, which was adapted from a later book.) And Hurt certainly does television.

The only thing I'm slightly disappointed about regarding this news is the fact that they're not doing Call for the Dead first. Though Call for the Dead (which was filmed in the Sixties as The Deadly Affair, also adapted by Dehn) features Smiley front and center and Spy does not, Spy is very much a sequel to Call. I wonder if Beaufoy will be able to incorporate certain aspects of that novel into his adaptation? Depending on how many episodes the miniseries turns out to be, that could be a very interesting approach.

What this news means for the Ink Factory's previously announced follow-up to The Night Manager, a 3-part adaptation of le Carre's 2003 novel Absolute Friends, remains to be seen. Hopefully that is still on track as well. (It may even materialize before The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.)

Read my book review of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold here.

Read my overview "George Smiley: An Introduction" here.

Labels:

Books,

John Le Carre,

Miniseries,

remakes,

Smiley,

Tradecraft,

TV

Apr 11, 2015

Gary Oldman's Tinker Tailor Sequel Headed to HBO?

It's been quite a while since we've heard anything on the Smiley front about a follow-up to Tomas Alfredson's fantastic 2011 Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (review here). More than two years ago, StudioCanal Chairman and CEO Olivier Courson revealed, "We are working on Smiley’s People with Working Title. It’s still at the development stage - but, yes, the old team of Peter Straughan and Tomas Alfredson is back together." Now, Tinker co-writer Straughan has just scripted Wolf Hall, the popular and well received miniseries adaptation of Hilary Mantel's bestselling novels about Thomas Cromwell and Henry VIII. The Writers Guild of America's official magazine, Written By, interviewed Straughan about the miniseries for their current issue, and in the course of the article casually drops this previously unreported tidbit: "Currently, [Straughan] is adapting the Le Carré novel Smiley's People for HBO. It's another huge task...." HBO? That's interesting! HBO was not involved in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, which was produced by StudioCanal and Working Title Films, and distributed in the U.S. by Focus Features. The film performed better and made more of a critical and cultural impact in Britain (where it won two BAFTA Awards) than the States, so I suppose it's possible that StudioCanal couldn't find a theatrical partner in the U.S. and instead opted for TV.

HBO has indeed proved a refuge lately for A-list filmmakers with adult projects. Steven Soderbergh famously made his dream project Liberace there after every film studio in town reportedly passed on a theatrical version despite the attachment of stars Michael Douglas and Matt Damon. It's also possible that HBO Films might be involved in a theatrical venture. While most of their theatrical features, like this summer's Entourage, are based on existing HBO shows, they did offer a limited run of the documentary Going Clear last month. The involvement of HBO also raises the intriguing question of whether the Seventies-set sequel, which Straughan has previously said would incorporate some elements of the second novel of the "Karla Trilogy," The Honourable Schoolboy, with the bulk (and title) of the third, Smiley's People, might emerge as a miniseries instead of a feature. It was, of course, previously filmed that way by the BBC in 1982. Personally, I would bet not. I would hazard a guess that we might be looking at a StudioCanal/Working Title/HBO co-production released theatrically in Britain and Europe and airing on HBO (perhaps in conjunction with a limited, Oscar-qualifying theatrical run) in the United States. But I would sure love some sort of official announcement that might shed some more light on the subject! It's a pity Written By didn't ask a follow-up question for clarification.

As long as the key team of Alfredson (Let the Right One In), Straughan (The Debt) and cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema (SPECTRE) all return, and key actors like Gary Oldman, Benedict Cumberbatch and Ciaran Hinds are involved, I don't much care if I see the sequel in a theater or on TV. Just so long as we get to see another Oldman Smiley movie! If HBO were to bring substantial extra funding to the equation, though, what I would really like to see would be the Hong Kong-set Honourable Schoolboy as that follow-up before concluding the trilogy with Smiley's People. Alas, it seems unlikely we'll ever see that masterpiece properly adapted due to cost issues. And I can hardly complain about a new version of Smiley's People, which is also a wonderful novel!

Read my article "George Smiley: An Introduction" here.

HBO has indeed proved a refuge lately for A-list filmmakers with adult projects. Steven Soderbergh famously made his dream project Liberace there after every film studio in town reportedly passed on a theatrical version despite the attachment of stars Michael Douglas and Matt Damon. It's also possible that HBO Films might be involved in a theatrical venture. While most of their theatrical features, like this summer's Entourage, are based on existing HBO shows, they did offer a limited run of the documentary Going Clear last month. The involvement of HBO also raises the intriguing question of whether the Seventies-set sequel, which Straughan has previously said would incorporate some elements of the second novel of the "Karla Trilogy," The Honourable Schoolboy, with the bulk (and title) of the third, Smiley's People, might emerge as a miniseries instead of a feature. It was, of course, previously filmed that way by the BBC in 1982. Personally, I would bet not. I would hazard a guess that we might be looking at a StudioCanal/Working Title/HBO co-production released theatrically in Britain and Europe and airing on HBO (perhaps in conjunction with a limited, Oscar-qualifying theatrical run) in the United States. But I would sure love some sort of official announcement that might shed some more light on the subject! It's a pity Written By didn't ask a follow-up question for clarification.

As long as the key team of Alfredson (Let the Right One In), Straughan (The Debt) and cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema (SPECTRE) all return, and key actors like Gary Oldman, Benedict Cumberbatch and Ciaran Hinds are involved, I don't much care if I see the sequel in a theater or on TV. Just so long as we get to see another Oldman Smiley movie! If HBO were to bring substantial extra funding to the equation, though, what I would really like to see would be the Hong Kong-set Honourable Schoolboy as that follow-up before concluding the trilogy with Smiley's People. Alas, it seems unlikely we'll ever see that masterpiece properly adapted due to cost issues. And I can hardly complain about a new version of Smiley's People, which is also a wonderful novel!

Read my article "George Smiley: An Introduction" here.

Jul 8, 2013

Upcoming Le Carre Blu-ray Titles

In the coming months, spy fans will be able to greatly expand their Blu-ray collections of John le Carré titles. In September, The Criterion Collection will issue The Spy Who Came In From the Cold on Blu, while this August Image will release The Tailor of Panama on BD and Acorn will release their long awaited Smiley's People Blu-ray.

Acorn's Blu-ray of the 1982 BBC miniseries starring Alec Guinness (in my opinion the finest le Carré adaptation yet produced—despite some really tough competition!) will not only mark the high-definition debut of Smiley's People in any region; it will also be the first time American viewers are able to see the additional hour of material cut from the original U.S. broadcast and all subsequent home video editions in this country! Like Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy before it, Smiley's People was reconfigured from seven episodes (as broadcast in Britain) to six for transmission on PBS's Masterpiece Theater. Since it would have been impossible to just drop an entire episode of this highly-complex spy story, this was done by shedding footage here and there from every episode. In the case of Tinker, Tailor, I feel that the trims actually streamlined the storytelling and improved the miniseries. (I would actually recommend the U.S. version over the British one.) However, in the case of Smiley's People, I feel that essential material was excised (including some of the miniseries' best scenes), and strongly prefer the UK broadcast version. The Blu-ray will not reinstate the missing footage into the narrative, but it will include all 62 minutes of it as deleted scenes, which is almost as good. These are deleted scenes well worth watching, and a special feature which will truly enhance the viewing experience! The Blu-ray will also include all of the extras from Acorn's previous DVD edition: a 20-minute interview with le Carré and text-based features like production notes, biographies and a useful glossary of the author's sometimes confusing spy jargon. This all-star sequel finds George Smiley (the incomparable Alec Guinness) once again coming out of retirement to take on his old Soviet nemesis Karla (Patrick Stewart) in a final battle of wits spanning Europe. It was filmed on location in London, Paris, Hamburg, and Bern, and co-stars Bernard Hepton (The Contract), Vladek Sheybal (From Russia With Love), Eileen Atkins (the Avengers movie), Michael Gough (the real Avengers) Anthony Bate (Game, Set and Match), Ingrid Pitt (Jason King), Andy Bradford (Octopussy), Curd Jürgens (The Spy Who Loved Me) Michael Lonsdale (Moonraker), Michael Byrne (Saracen), Lucy Fleming (Cold Warrior—and, yes, that's Lucy Fleming as in niece of Ian, whose best scene can be found amongst that deleted material), and a scene-stealing Beryl Reid (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy). It's absolutely essential viewing, and this Blu-ray will be a requirement in any spy collection worth its salt! Retail is $59.99, but luckily Amazon has it for pre-order for much less. It streets on August 6.

Also out in August (August 20 to be precise) is Image's new Blu-ray of John Boorman's vastly underrated 2001 film of The Tailor of Panama starring Pierce Brosnan and Geoffrey Rush. The film mines unusually (though naturally dark) comedic territory for le Carré, and does a damn fine job of it. (It's really the author's variation on Graham Greene's Our Man in Havana.) It also features my favorite Pierce Brosnan performance ever. Really, he's unmissable in this, making it a must for Bond fans as well as le Carré fans. The Blu-ray from Image will carry over all of the special features from Columbia's DVD, including a Boorman commentary track, an alternate ending with optional commentary, theatrical trailers, and the featurette "The Perfect Fit: A Conversation with Pierce Brosnan and Geoffrey Rush." Unfortunately, the Blu-ray utilizes the same slapdash cover art as the DVD instead of the film's fantastic illustrated poster, but that's to be expected these days. Retail is just $17.97, and you can pre-order it from Amazon for even less.

Acorn's Blu-ray of the 1982 BBC miniseries starring Alec Guinness (in my opinion the finest le Carré adaptation yet produced—despite some really tough competition!) will not only mark the high-definition debut of Smiley's People in any region; it will also be the first time American viewers are able to see the additional hour of material cut from the original U.S. broadcast and all subsequent home video editions in this country! Like Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy before it, Smiley's People was reconfigured from seven episodes (as broadcast in Britain) to six for transmission on PBS's Masterpiece Theater. Since it would have been impossible to just drop an entire episode of this highly-complex spy story, this was done by shedding footage here and there from every episode. In the case of Tinker, Tailor, I feel that the trims actually streamlined the storytelling and improved the miniseries. (I would actually recommend the U.S. version over the British one.) However, in the case of Smiley's People, I feel that essential material was excised (including some of the miniseries' best scenes), and strongly prefer the UK broadcast version. The Blu-ray will not reinstate the missing footage into the narrative, but it will include all 62 minutes of it as deleted scenes, which is almost as good. These are deleted scenes well worth watching, and a special feature which will truly enhance the viewing experience! The Blu-ray will also include all of the extras from Acorn's previous DVD edition: a 20-minute interview with le Carré and text-based features like production notes, biographies and a useful glossary of the author's sometimes confusing spy jargon. This all-star sequel finds George Smiley (the incomparable Alec Guinness) once again coming out of retirement to take on his old Soviet nemesis Karla (Patrick Stewart) in a final battle of wits spanning Europe. It was filmed on location in London, Paris, Hamburg, and Bern, and co-stars Bernard Hepton (The Contract), Vladek Sheybal (From Russia With Love), Eileen Atkins (the Avengers movie), Michael Gough (the real Avengers) Anthony Bate (Game, Set and Match), Ingrid Pitt (Jason King), Andy Bradford (Octopussy), Curd Jürgens (The Spy Who Loved Me) Michael Lonsdale (Moonraker), Michael Byrne (Saracen), Lucy Fleming (Cold Warrior—and, yes, that's Lucy Fleming as in niece of Ian, whose best scene can be found amongst that deleted material), and a scene-stealing Beryl Reid (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy). It's absolutely essential viewing, and this Blu-ray will be a requirement in any spy collection worth its salt! Retail is $59.99, but luckily Amazon has it for pre-order for much less. It streets on August 6.

Also out in August (August 20 to be precise) is Image's new Blu-ray of John Boorman's vastly underrated 2001 film of The Tailor of Panama starring Pierce Brosnan and Geoffrey Rush. The film mines unusually (though naturally dark) comedic territory for le Carré, and does a damn fine job of it. (It's really the author's variation on Graham Greene's Our Man in Havana.) It also features my favorite Pierce Brosnan performance ever. Really, he's unmissable in this, making it a must for Bond fans as well as le Carré fans. The Blu-ray from Image will carry over all of the special features from Columbia's DVD, including a Boorman commentary track, an alternate ending with optional commentary, theatrical trailers, and the featurette "The Perfect Fit: A Conversation with Pierce Brosnan and Geoffrey Rush." Unfortunately, the Blu-ray utilizes the same slapdash cover art as the DVD instead of the film's fantastic illustrated poster, but that's to be expected these days. Retail is just $17.97, and you can pre-order it from Amazon for even less.

Meanwhile, Criterion's Spy Who Came in from the Cold Blu-ray includes a new, high-definition digital restoration of Martin Ritt's seminal 1965 Richard Burton movie with an uncompressed monaural soundtrack along with all the excellent special features found on the existing DVD edition: a wide-ranging video interview with le Carré (thoroughly engrossing, but beware of spoilers for some of his other works), a selected-scene commentary featuring director of photography Oswald Morris, the 2000 BBC documentary The Secret Center: John le Carré (while essential viewing for fans, this is also a bit spoilery, as it contains extensive clips from the BBC le Carré productions Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, Smiley's People [including the very end] and A Perfect Spy), a 1967 Richard Burton interview, an audio conversation from 1985 between director Martin Ritt and film historian Patrick McGilligan, a gallery of set designs, the trailer and a booklet featuring an essay by critic Michael Sragow. The gritty, black and white adaptation of le Carré's most famous novel reunited Burton with his Look Back in Anger co-star Claire Bloom and featured Rupert Davies as the screen's first Smiley. The disc is out September 10 and retail is $39.95, though again it's significantly less to pre-order on Amazon.

Since as of now The Deadly Affair, The Looking Glass War and The Little Drummer Girl are only available as MOD discs, I can't envision any of them becoming available in high-def editions any time soon. But for the time being, these three new titles should make excellent additions to any le Carré Blu-ray collection, and look great alongside your Blu-rays of the two versions of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (BBC and 2011 feature) and maybe your region-free import copy of The Constant Gardener.

Read my "Introduction to George Smiley" here.

Feb 10, 2013

Update On Le Carre Movies in Development, Including Smiley Sequel

Screen Daily (via Dark Horizons) has an update on a pair of John le Carré movies from StudioCanal that we've been eagerly following for a while: Our Kind of Traitor and the sequel to 2011's Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. We already knew that Australian director Justin Kurzel was helming the adaptation of Traitor, le Carré's most recent novel to date (though there's another one coming this year!), and that Bond alumni Mads Mikkelson and Ralph Fiennes were attached to star (as the charismatic Russian gangster Dima and the zealous British intelligence chief Hector, respectively). Now the trade reports that Ewan McGregor has signed on to star as Perry, a young, tenure-track English academic adrift, searching for something apparently unattainable that will make him what he calls a "formed man." His girlfriend, Gail, is the crucial role yet to be cast. And she's a great character—perhaps the author's best female character to date. It's a terrific part awaiting some very lucky actress. (Jessica Chastain was rumored at one point.) Production on the $35 million movie is scheduled for a summer start in Moscow, Marrakesh, Paris, London and Switzerland. Producer Simon Cornwell (le Carré's son) pointed out to Screen that unlike Tinker Tailor and the upcoming A Most Wanted Man (starring Phillip Seymour Hoffman), Our Kind of Traitor focuses on "an everyman couple" caught up in the treacherous world of espionage, promising "exciting scale and accessibility." So far, this is shaping up to look like another fantastic le Carré adaptation!

Meanwhile, Screen also pressed StudioCanal Chairman and CEO Olivier Courson for an update on the eagerly anticipated follow-up to Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Confirming what many others involved have already indicated, that they will follow the BBC's example and sadly skip the stellar middle volume in the Karla Trilogy, The Honourable Schoolboy, Courson revealed, “We are working on Smiley’s People with Working Title. It’s still at the development stage - but, yes, the old team of Peter Straughan and Tomas Alfredson is back together. The same Tinker Tailor actors whose characters would reappear are well aware of what we’re doing. We’re hopeful for a 2014 shoot.” Well, I would have dearly liked to see Schoolboy finally filmed, but the fact that the studio and the same creative team remain committed to filming another Smiley movie is still fantastic news indeed! They did an amazing job on Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (read my review here), and I can't wait to see Gary Oldman slip into Smiley's spectacles once more.

Meanwhile, Screen also pressed StudioCanal Chairman and CEO Olivier Courson for an update on the eagerly anticipated follow-up to Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Confirming what many others involved have already indicated, that they will follow the BBC's example and sadly skip the stellar middle volume in the Karla Trilogy, The Honourable Schoolboy, Courson revealed, “We are working on Smiley’s People with Working Title. It’s still at the development stage - but, yes, the old team of Peter Straughan and Tomas Alfredson is back together. The same Tinker Tailor actors whose characters would reappear are well aware of what we’re doing. We’re hopeful for a 2014 shoot.” Well, I would have dearly liked to see Schoolboy finally filmed, but the fact that the studio and the same creative team remain committed to filming another Smiley movie is still fantastic news indeed! They did an amazing job on Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (read my review here), and I can't wait to see Gary Oldman slip into Smiley's spectacles once more.

Dec 14, 2012

Smiley Sequel Still in the Works

Last year, while doing the press rounds promoting Tomas Alfredson's brilliant Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (review here), both star Gary Oldman and screenwriter Peter Straughan (who penned the film with his late wife Bridget O'Connor) let slip that they'd be keen on making a sequel. Both men mentioned John le Carré's third novel in the so-called "Karla Trilogy," Smiley's People, as the likely inspiration for such, skipping over the brilliant middle novel, The Honourable Schoolboy, just like the BBC did decades ago with their miniseries. That's a shame, because in my opinion Schoolboy would make a great film. Straughan told me that the main reason for that was the same as the BBC's reason in the Eighties: the high cost associated with shooting on location in Hong Kong, where the bulk of the novel takes place. It would be even worse now than it was then, as the story is now a period piece. But he did say that a potential follow-up film would likely incorporate certain aspects of The Honourable Schoolboy into the overall story of Smiley's People. A lot of websites keep perpetuating the notion that Smiley isn't much of a presence in Schoolboy, and cite that as the reason it will likely be skipped. That's baloney. While it's true that Jerry Westerby is the main character in the book, Smiley sees just about as much action in Schoolboy as he did in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. It's a longer book. It could easily be adapted in such a way as to focus on the Smiley sections, thus beefing up Oldman's role. But all that's moot because of the cost issue anyway. Sadly.

So that was a year ago. Since then, a lot of time has passed without any further mention of a Smiley sequel. I was starting to fear that it had fallen by the wayside. But luckily Collider (via Dark Horizons) was recently on the spot to get a comment from producer Eric Fellner, and he assured them that work on the follow-up continues apace, albeit quietly! "We are working on another one," Fellner told the website. "Tim Bevan [his producing partner] is putting it together as we speak with Peter Straughan and Tomas Alfredson, so yes it’s in development." Hurrah! I'm happy to hear it! "But things take time," he then adds. "Tim is passionate about making sure we do another one." Well, thank you, Tim! Schoolboy or Smiley's People, I can't wait to see Alfredson return to le Carré's Circus and Oldman reprise his role as the inimitable spymaster George Smiley.

Nov 13, 2012

Book Review: Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy by John le Carré (1974)

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy is probably the most famous book in the Smiley series, and deservedly so. Once again, Smiley is retired (as in Call For the Dead and, apparently, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold), and once again he is summoned out of that retirement, this time by the Cabinet Office’s Oliver Lacon, the bureaucrat charged with oversight of British Intelligence. Lacon charges Smiley with the task of ferreting out a mole in the organization. Everyone who works there now, including the four-man cabal running things, is a suspect. Smiley himself is in the clear only by virtue of his having been drummed out of the Circus (as le Carré refers to the Secret Service) a year prior following the ouster of the department’s longtime ringmaster Control. Control (since deceased) went somewhat bonkers in his final year, paranoid and obsessed with discovering the leak in his organization. With the aid of trustworthy confidante Peter Guillam (still officially employed by the Circus, but exiled to an outstation by the new regime), Smiley picks up where his late mentor left off and quickly determines that the mole has to be one of four men, all former colleagues of his: Bill Haydon, Roy Blunt, Toby Esterhase or Percy Alleline—the latter now occupying Control’s old position.

I’ll be honest: I love this book so much that I find it daunting to write about. John le Carré’s 1974 novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy is not only my favorite spy novel, but my favorite novel—period. I’m in awe of it. Every time I re-read it, it’s rewarding anew, revealing new secrets hidden within the labyrinthine folds of the author’s elegant, perfectly crafted prose. It’s at once comfortingly familiar and joltingly fresh every time. Even though I know the outcome, I always get caught up in spymaster George Smiley’s quest to root out a mole among his friends and former colleagues in the stuffy, lived-in halls of the British Secret Service.

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy is the ideal combination of perfectly constructed prose and plot. Le Carré’s language is always amazing, but in particularly fine form in this book. He’s famous for his spy jargon—more invented than recalled from his own days in the secret world, but with such a ring of authenticity that many of his terms, like “mole,” have not only turned up in the fiction of other writers, but entered into the actual lexicon of the trade—but it’s his peerless sentence construction and turns of phrase that hook me more than that. Smiley’s right-hand man, Peter Guillam, for example, identifies his mentor’s particular talents for unraveling intrigue and subterfuge as Smiley’s “devious arithmetic.” Smiley himself reflects, with typical self deprecation, that “it is sheer vanity to believe that one fat middle-aged spy is the only person capable of holding the world together.” (This sentence is so unforgettable that Olen Steinhauer effectively resurrects it by way of homage in his own espionage masterwork An American Spy.)

Even more impressive than his sentence construction, however, is le Carré’s astoundingly intricate plot construction—his own devious arithmetic. Just as le Carré perfectly assembles words into mellifluous, multi-layered sentences, so he assembles those sentences into an equally multi-layered plot of staggering nuance and complexity. The book is put together like a puzzle. Rather than a traditional, straightforward narrative, readers are doled out individual pieces (or sometimes partially assembled sections), but the story still flows like a traditional narrative, always driven forward by Smiley’s dogged present-day investigation. That investigation consists largely of him in a hotel room, meticulously scouring old files through all hours of the night… but scouring old files has never been so exciting! (I gasp aloud every time I come to the ingenious final “knot” in Moscow spymaster Karla's master plan.)

The files he reads, summarized for us in prose far preferable to that of actual government reports, are augmented by copious portions of Smiley’s own memories. The memories and the official record intermingle to tell a story driven in equal parts by recorded facts and emotional connections—neither of which we, or Smiley, are ever certain we can trust. Le Carré is often cited for his frequent use of in medias res (beginning in the middle of things), but the actual cumulative effect of this sort of multi-tiered storytelling goes well beyond that. In the case of Tinker, Tailor, the entire novel seems to occur at once. Although the thick book is by no means a quick read, the effect of reading it seems to me like instantly downloading an entire drive’s worth of information into my brain. There is so much information—not merely expository, but also emotional—that every chapter, every sequence, every sentence appears to be packed with more than one piece. What impressed me most about Tomas Alfredson’s 2011 movie adaptation wasn’t its fidelity to the plot of the novel (many scenes were necessarily excised or altered completely), but its incredible fidelity to this highly effective narrative technique. To paraphrase my film review, screenwriters Bridget O’Connor and Peter Straughan managed the impressive feat of “unpacking” all of le Carré’s loaded chapters and sentences and then repacking them in even smaller units for the film’s roughly 2-hour runtime.

This storytelling style isn’t limited to scenes told from Smiley’s perspective. There’s no better demonstrative microcosm of le Carré’s complex whole than the breathtaking sequence in which Peter Guillam (sent by Smiley) must covertly retrieve the top secret “Operation Testify” file from the Circus archives—right out from under the noses of Smiley’s suspects. Through subterfuge and sleight of hand, Guillam manages to remove the file and smuggle it out of the archive while being watched, but then finds himself summoned by Toby Esterhase into a meeting of Circus honchos who know that Guillam is hiding something from them—but aren’t sure what. We get Guillam’s point of view the whole time, and his mind is wandering. It’s all happening in the now, but at the same time he’s thinking of how Smiley will react in the future (Smiley would want to know who was in the meeting), what Smiley told him in the near past about the scheme, his own current lover Camilla, and his own further distant past, with regards to his predecessor Jim Prideaux (chief protagonist of Operation Testify, since wounded and disavowed) and his defunct Moroccan networks (blown by the mole), which must always weigh heavily on his mind. But these thoughts all, realistically, seem like parts of the now, and not extraneous flashbacks that take us away from the scene we’re in. Instead they all add to it; they’re all part of it, and the perfect concoction thereof makes the scene that much more suspenseful. It’s spy fiction at its very best.

Of course, the whole novel is spy fiction at its very best. Within it, le Carré manages to cover almost every aspect of the espionage trade, from uncovering moles to penetration to turning defectors to intelligence gathering and distribution to running networks to blowing networks to crossing borders to forged passports to surveillance (“lamplighter” work in le Carré’s world) to counter-surveillance to secret filing and bureaucracy to, yes, even “scalphunter” work: black bag missions and gunfire. There are even gadgets, if you count the wired walls in the “Witchcraft” safe house! Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy truly has it all. Sure, it’s a long, long way from Doctor No, but fans of the Fleming side of the spy genre may find themselves in more familiar territory here than they suspect, and every spy fan, whether they prefer serious or silly, desk men or field men, should read this book. It's simply without equal.

The Smiley Files

Part 1: George Smiley: An Introduction

Part 2: Movie Review: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Part 3: Book Review: Call for the Dead (1961)

Part 4: Movie Review: The Deadly Affair (1966)

Part 5: Book Review: A Murder of Quality (1962)

Part 6: Movie Review: A Murder of Quality (1991)

Part 7: Book Review: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963)

Part 8: Book Review: The Looking Glass War (1965)

Apr 17, 2012

Book Review: The Looking Glass War by John le Carré (1965)

Book Review: The Looking Glass War by John le Carré (1965)

Critics in 1965 saw The Looking Glass War as something of a departure for John le Carré following the breakout universal success of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. In his 1990s introduction to the book, the author claims they weren’t happy about that—not in Britain anyway. Everyone wanted the same thing from him again, and he wanted to give them something different. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold had depicted in great detail a highly successful and wickedly clever espionage operation masterminded by a man called Control, the ingenious head of an intelligence service known as “the Circus.” Le Carré claims that operations of that sort were not quite what he himself experienced during his years as a spook, during which he worked for both MI5 and MI6. In his follow-up novel, he wanted to present something much closer to the truth as he knew it: a clumsily planned operation carried out by well-meaning fools with delusions of grandeur still fighting the last war in their heads, who haven’t yet learned to properly use the tools of the new (Cold) one. A story of vital opportunities—not to mention lives—lost because of career bureaucrats more focused on inter-agency bickering than gathering good intelligence.

Not only did le Carré change his presentation of the British intelligence establishment; he even changed his tone, trading in the bleak, urgent paranoia of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold for extra-dry satire with a vicious bite. (Somewhat reminiscent of his take on another British institution, the public school, in A Murder of Quality.) The new approach caught contemporary critics and readers off guard. If he had it to do again, le Carré writes in his introduction, he would probably opt to leave out returning characters like Control and George Smiley altogether, along with any mention of the Circus, presumably so as to firmly set The Looking Glass War in its own separate literary universe and not raise false expectations in readers familiar with his previous work. Thank goodness he didn’t get the opportunity to do it again, like he did with A Murder of Quality (when he penned the screenplay for its 1991 TV adaptation)! The Looking Glass War is a very good novel as it stands now, and some of the best moments and sharpest satire come directly from his use of those pre-established characters and organizations.

Never mentioning real-world monikers like “MI6” or “SIS,” le Carré always refers to George Smiley’s organization simply as “the Circus.” Likewise, the arm of the intelligence establishment explored in The Looking Glass War is also known only by a colloquialism: “the Department.” (This could be a little confusing to readers of the author’s wider Smiley series, since the Circus itself is often referred to as “the Department” as well in other novels, but for the purposes of The Looking Glass War, those names refer strictly to two very different intelligence agencies.) The Department is concerned exclusively with intelligence on military targets, and though it ran a lot of missions during WWII (sort of like the SOE, I guess), its primary concern by the 1960s is analysis rather than intelligence gathering. It’s an old department housed in an old building and made up of old men, all veterans of those halcyon days of the War… except for one.

The protagonist is John Avery, the Department’s youngest employee and as such its rising star. Avery is the aide to the Director of the Department, Leclerc. Leclerc is fed up with seeing his former responsibilities one by one subsumed by the Circus. He longs to return his organization to its wartime strength, and sees an opportunity to do just that when one of his few remaining field men (all remnants of defunct wartime networks, naturally) turns in a report containing a defector’s eyewitness account of Soviet missiles being secretly installed in a rural part of East Germany. Rather than turning this report over to the Circus for some sort of corroboration, Leclerc becomes fiercely territorial, claims that since the potential target is military, it is his purview, and launches his own operation. The first agent dispatched (to meet an asset in Finland) turns up dead, which in itself is enough in Leclerc’s mind to confirm that his suspicions are correct and there’s a basis for further action. Leclerc declares that the Department will have to send a man in, behind the Iron Curtain, to obtain confirmation of the intel.

Standard contemporary protocol would dictate turning over such a mission to the Circus, who have many experienced field men used to exactly that sort of assignment. (In fact, Alec Leamas even gets a mention as a potential candidate!) But pride and jealousy prevent Leclerc from doing that. Officially, he convinces his Ministry that mixing up the two agencies’ purviews would create a “monolith,” but his real reasons are less civic-minded: he wants a chauffeured car like the one Control has. He wants a budget like Control’s. He wants a building that’s not falling apart. In short, he wants to command the same respect he imagines that Control commands.

These moments of interdepartmental jealousy are highlights of the novel for students of le Carré’s oeuvre, and they work specifically because readers are already familiar with the organizations and characters in question. We know from previous books that the people who work at the Circus don’t consider it to be very luxurious or well-heeled itself. (There isn’t even a budget to keep its headquarters properly heated in the winter!) So to then see a flipside of that, to realize that there are other departments even worse off who see the Circus’s grass as so much greener, provides the reader with both comedy and instant identification. How many of us have not had similar moments of professional jealousy at our own jobs? Half the joke would be lost if we didn’t already know that Control has to light a fire himself if he wants his office to warm up, and that Smiley has to deal with image-conscious idiots like Maston who would happily allow an enemy spy to remain at large for the sake of avoiding embarrassment. Le Carré is able to take advantage of his own canon to provide helpful shorthand in his satire. For all of Smiley’s misery in his job, who would have guessed that there are others in his profession even worse off?

Leclerc and his team dig deep into the Department files and recruit a Polish-born agent who served them well during the War named Leiser. He seems (to them, anyway) the perfect man to penetrate the East. Avery is tasked with babysitting him during his training. But more than that, it’s his role to form a bond with Leiser. Leclerc and his more worldly-wise associate, Haldane, understand that such a bond is integral in fostering an agent’s loyalty. Avery doesn’t realize that he’s being used in this manner.

Seasoned spy readers (especially those familiar with Graham Greene's Our Man in Havana or le Carré's own later reworking of that story, The Tailor of Panama) will spot enough obvious clues along the way to be reasonably sure going into Part III of the novel's three parts that the original intelligence is probably bad, and there will be no missiles, which causes the story to lose a bit of momentum as it follows Leiser on what we strongly suspect is a fool’s errand. But the section leading up to what we’re sure will be a disaster is rich in both character and satire. We witness with equal parts humor and dread as Leiser is trained by experts the Department has dragged out of their comfortable civilian lives to teach the same techniques they taught or used during the War. In one respect, The Looking Glass War sets the template (more than The Spy Who Came in from the Cold) for future le Carré novels: we know from the start that the idealistic protagonist (or one of them, anyway) is doomed in this world, and the big question of the novel is not if that doom will come but how. While the author frequently plays this scenario for dread, here he plays it more for dark comedy. He doesn’t comment on what Leclerc and his Department do wrong; instead he makes it obvious even to people (the majority of his readers, presumably) with no experience in the intelligence field. It’s like watching a car crash in slow motion. We can’t stop it, but we’re fascinated by it nonetheless.

The Looking Glass War isn’t all dark comedy, however. It functions on two levels: as a very sharp satire, and, only slightly less successfully, as a love story between two heterosexual men, Leiser and Avery. Their bond isn’t a homosexual bond like that between Hayden and Prideaux in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy; it’s a deep platonic connection. And, for these two lonely men at this particular place and time, it proves to be a deeper connection than they share with the women in their lives. A part of Leiser knows that he’s going to his doom (in some sense of the word, anyway; “doom” doesn’t necessarily imply “death”), but for Avery, he will willingly do so. That’s exactly what Leclerc and Haldane are counting on, and it makes The Looking Glass War as much a tragedy as a comedy. Again, that leads me to believe that the inclusion of Smiley and Control was integral to the book. Without them, the best comic elements would have been lost, and the story would have risked turning too bleak.

As for Smiley, he actually gets considerably more “screen time” in this novel than he did in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, though his role is less integral to the overall mechanics of the story, if not the tone. He’s also clearly Control’s right-hand man at the Circus, which makes this our only glimpse of the era referred to so frequently in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, when the two enjoyed a successful partnership at the helm of the ship. Smiley has no cause to resign, for once, though he does have the regrettable task of delivering some very bad news. Despite the character’s limited appearance, The Looking Glass War is not a book that Smiley fans should pass over, nor is it a novel that fans of le Carré should overlook. When it comes to Smiley, however, the best (of course), was still yet to come...

The Smiley Files

Part 1: George Smiley: An Introduction

Part 2: Movie Review: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

Part 3: Book Review: Call for the Dead (1961)

Part 4: Movie Review: The Deadly Affair (1966)

Part 5: Book Review: A Murder of Quality (1962)

Part 6: Movie Review: A Murder of Quality (1991)

Part 7: Book Review: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963)

Critics in 1965 saw The Looking Glass War as something of a departure for John le Carré following the breakout universal success of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. In his 1990s introduction to the book, the author claims they weren’t happy about that—not in Britain anyway. Everyone wanted the same thing from him again, and he wanted to give them something different. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold had depicted in great detail a highly successful and wickedly clever espionage operation masterminded by a man called Control, the ingenious head of an intelligence service known as “the Circus.” Le Carré claims that operations of that sort were not quite what he himself experienced during his years as a spook, during which he worked for both MI5 and MI6. In his follow-up novel, he wanted to present something much closer to the truth as he knew it: a clumsily planned operation carried out by well-meaning fools with delusions of grandeur still fighting the last war in their heads, who haven’t yet learned to properly use the tools of the new (Cold) one. A story of vital opportunities—not to mention lives—lost because of career bureaucrats more focused on inter-agency bickering than gathering good intelligence.

Not only did le Carré change his presentation of the British intelligence establishment; he even changed his tone, trading in the bleak, urgent paranoia of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold for extra-dry satire with a vicious bite. (Somewhat reminiscent of his take on another British institution, the public school, in A Murder of Quality.) The new approach caught contemporary critics and readers off guard. If he had it to do again, le Carré writes in his introduction, he would probably opt to leave out returning characters like Control and George Smiley altogether, along with any mention of the Circus, presumably so as to firmly set The Looking Glass War in its own separate literary universe and not raise false expectations in readers familiar with his previous work. Thank goodness he didn’t get the opportunity to do it again, like he did with A Murder of Quality (when he penned the screenplay for its 1991 TV adaptation)! The Looking Glass War is a very good novel as it stands now, and some of the best moments and sharpest satire come directly from his use of those pre-established characters and organizations.

Never mentioning real-world monikers like “MI6” or “SIS,” le Carré always refers to George Smiley’s organization simply as “the Circus.” Likewise, the arm of the intelligence establishment explored in The Looking Glass War is also known only by a colloquialism: “the Department.” (This could be a little confusing to readers of the author’s wider Smiley series, since the Circus itself is often referred to as “the Department” as well in other novels, but for the purposes of The Looking Glass War, those names refer strictly to two very different intelligence agencies.) The Department is concerned exclusively with intelligence on military targets, and though it ran a lot of missions during WWII (sort of like the SOE, I guess), its primary concern by the 1960s is analysis rather than intelligence gathering. It’s an old department housed in an old building and made up of old men, all veterans of those halcyon days of the War… except for one.

The protagonist is John Avery, the Department’s youngest employee and as such its rising star. Avery is the aide to the Director of the Department, Leclerc. Leclerc is fed up with seeing his former responsibilities one by one subsumed by the Circus. He longs to return his organization to its wartime strength, and sees an opportunity to do just that when one of his few remaining field men (all remnants of defunct wartime networks, naturally) turns in a report containing a defector’s eyewitness account of Soviet missiles being secretly installed in a rural part of East Germany. Rather than turning this report over to the Circus for some sort of corroboration, Leclerc becomes fiercely territorial, claims that since the potential target is military, it is his purview, and launches his own operation. The first agent dispatched (to meet an asset in Finland) turns up dead, which in itself is enough in Leclerc’s mind to confirm that his suspicions are correct and there’s a basis for further action. Leclerc declares that the Department will have to send a man in, behind the Iron Curtain, to obtain confirmation of the intel.

Standard contemporary protocol would dictate turning over such a mission to the Circus, who have many experienced field men used to exactly that sort of assignment. (In fact, Alec Leamas even gets a mention as a potential candidate!) But pride and jealousy prevent Leclerc from doing that. Officially, he convinces his Ministry that mixing up the two agencies’ purviews would create a “monolith,” but his real reasons are less civic-minded: he wants a chauffeured car like the one Control has. He wants a budget like Control’s. He wants a building that’s not falling apart. In short, he wants to command the same respect he imagines that Control commands.

These moments of interdepartmental jealousy are highlights of the novel for students of le Carré’s oeuvre, and they work specifically because readers are already familiar with the organizations and characters in question. We know from previous books that the people who work at the Circus don’t consider it to be very luxurious or well-heeled itself. (There isn’t even a budget to keep its headquarters properly heated in the winter!) So to then see a flipside of that, to realize that there are other departments even worse off who see the Circus’s grass as so much greener, provides the reader with both comedy and instant identification. How many of us have not had similar moments of professional jealousy at our own jobs? Half the joke would be lost if we didn’t already know that Control has to light a fire himself if he wants his office to warm up, and that Smiley has to deal with image-conscious idiots like Maston who would happily allow an enemy spy to remain at large for the sake of avoiding embarrassment. Le Carré is able to take advantage of his own canon to provide helpful shorthand in his satire. For all of Smiley’s misery in his job, who would have guessed that there are others in his profession even worse off?

Leclerc and his team dig deep into the Department files and recruit a Polish-born agent who served them well during the War named Leiser. He seems (to them, anyway) the perfect man to penetrate the East. Avery is tasked with babysitting him during his training. But more than that, it’s his role to form a bond with Leiser. Leclerc and his more worldly-wise associate, Haldane, understand that such a bond is integral in fostering an agent’s loyalty. Avery doesn’t realize that he’s being used in this manner.

Seasoned spy readers (especially those familiar with Graham Greene's Our Man in Havana or le Carré's own later reworking of that story, The Tailor of Panama) will spot enough obvious clues along the way to be reasonably sure going into Part III of the novel's three parts that the original intelligence is probably bad, and there will be no missiles, which causes the story to lose a bit of momentum as it follows Leiser on what we strongly suspect is a fool’s errand. But the section leading up to what we’re sure will be a disaster is rich in both character and satire. We witness with equal parts humor and dread as Leiser is trained by experts the Department has dragged out of their comfortable civilian lives to teach the same techniques they taught or used during the War. In one respect, The Looking Glass War sets the template (more than The Spy Who Came in from the Cold) for future le Carré novels: we know from the start that the idealistic protagonist (or one of them, anyway) is doomed in this world, and the big question of the novel is not if that doom will come but how. While the author frequently plays this scenario for dread, here he plays it more for dark comedy. He doesn’t comment on what Leclerc and his Department do wrong; instead he makes it obvious even to people (the majority of his readers, presumably) with no experience in the intelligence field. It’s like watching a car crash in slow motion. We can’t stop it, but we’re fascinated by it nonetheless.

The Looking Glass War isn’t all dark comedy, however. It functions on two levels: as a very sharp satire, and, only slightly less successfully, as a love story between two heterosexual men, Leiser and Avery. Their bond isn’t a homosexual bond like that between Hayden and Prideaux in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy; it’s a deep platonic connection. And, for these two lonely men at this particular place and time, it proves to be a deeper connection than they share with the women in their lives. A part of Leiser knows that he’s going to his doom (in some sense of the word, anyway; “doom” doesn’t necessarily imply “death”), but for Avery, he will willingly do so. That’s exactly what Leclerc and Haldane are counting on, and it makes The Looking Glass War as much a tragedy as a comedy. Again, that leads me to believe that the inclusion of Smiley and Control was integral to the book. Without them, the best comic elements would have been lost, and the story would have risked turning too bleak.